|

Between 1969 and 1975, American author Roger Zelazny (1937 - 1995) wrote three stories featuring a nameless trouble-shooting protagonist in a highly computerised future. The book My Name Is Legion collects all three of these tales, the third of which won both the Hugo and Locus awards for Best Novella in 1976.

Today, Zelazny is best known for his Chronicles of Amber fantasy series, published between 1970 and 1991, and to a certain extent for his influential post-apocalyptic science fiction novel Damnation Alley (1969). The stories collected in My Name Is Legion are an interesting, if uneven, window into Zelazny’s short fiction.

The essential premise of the series is that by some point in the 21st century, global society is organised around a “Central Data Bank”. Like other SF authors of the time, Zelazny extrapolated the contemporary developments in computing into a monolithic, centralised system. This stands in contrast to the messier, distributed structure of the Internet. The protagonist of the stories was one of the architects of this centralised system, which ostensibly collects the medical, financial, travel, employment, and other records of everyone on Earth.

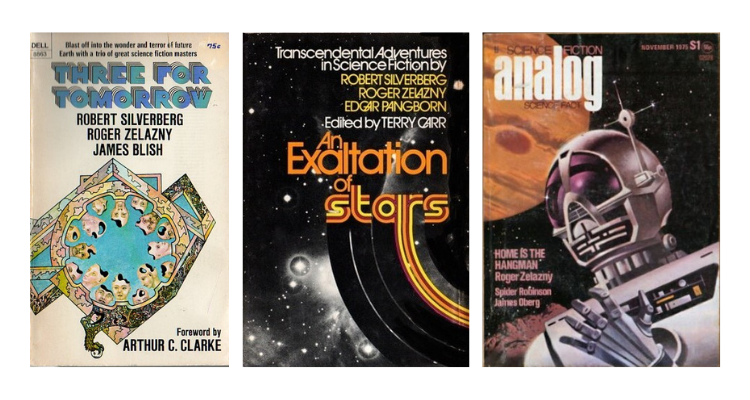

Shortly before the system went online, the protagonist was given the opportunity to opt-out. By taking up this offer, he became a kind of “non-person”, his every record expunged from the database. Later, he contrived a backdoor into the system and obtained the ability to produce new identities for himself at will. Still needing a means to support himself financially, he joins a private detective agency, which exploits his ability to assume new identities and to blend in. The three novellas in My Name Is Legion each recount a specific mission in the career of this resourceful “non-person”. While the stories were originally published separately over several years, later ones consistently mention the earlier ones and there is a sense of continuity. The first story, “The Eve of RUMOKO”, was originally published in the anthology Three for Tomorrow in 1969. The book also contains novellas by James Blish and Robert Silverberg (who also edited it), and features a foreword by Arthur C. Clarke. The story introduces Zelazny’s nameless protagonist, and explains how he came to be a protean “non-person”. By the time the story begins, he has been working as a covert troubleshooter for some time. In this instance, he assumes the identity of Albert Schweitzer, a technician on the experimental Project RUMOKO. This initiative aims to use nuclear shaped charges, drilled into the seafloor, to trigger controlled releases of magma and to create man-made volcanic islands. Despite this quite fanciful concept, “The Eve of RUMOKO” is a relatively banal kind of SF detective story. Schweitzer is tasked with preventing the sabotage of the project, and proves to be more than up to the task. The more interesting aspect is how surprisingly ruthless the protagonist can be. He exploits his unique position to take steps that could significantly alter the course of world events, and will have dramatic human costs.

The second story, which has the bizarre title “'Kjwalll'kje'k'koothaïlll'kje'k”, was also published in a three-story multi-author anthology. Edited by Terry Carr, the book An Exaltation of Stars was published in the summer of 1973. It also contains a story by Silverberg, and one of the last works by Edgar Pangborn, who died in 1976.

Now using the name Madison, Zelazny’s protagonist is dispatched to a kind of aquatic nature reserve which uses sonic emitters to control the movements of marine life. Madison’s employers ask him to investigate the cause of a violent death at the facility, and ideally to prove that the killing was not the work of a group of dolphins. What marks this second mission out is that the SF element is slight, at least until the end. Rather sadly, dolphins play almost no part in the story The final story, “Home is the Hangman”, was published in the November 1975 issue of Analog. It was highly successful - not only did it win the Hugo and Locus Awards, it also came second in the run for the equivalent Nebula Award. It is easy to see why, as this is by far the strongest story of the set. For his third mission, our dubious antihero takes on the name John Donne, after the English poet (1572 - 1631). He is hired to learn the truth about the “Hangman”, a humanoid, remotely-piloted machine designed for space exploration. It disappeared on a mission years earlier, but has since crash-landed back on Earth. The Hangman has apparently become self-aware, and is seemingly hunting down the four people who created and programmed it. This is a problem, given that the machine is nearly indestructible. Donne ends up interviewing the Hangman’s creators, who live in various locations around the United States. All the while, the implacable machine closes in on its targets. “Home is the Hangman” could easily have been a fast-paced, all-action story and that would no doubt have been entertaining - after all, Zelazny achieved that with Damnation Alley. Instead, he tells it in a more meditative way, rich with philosophy and a strong emphasis on the concepts of guilt and responsibility. The ending is clever and surprising, and caps off the whole book in a satisfying way. My Name is Legion is definitely a mixed bag, but is worth reading in full if only for the way the earlier stories build up to the excellent finale of “Home is the Hangman”, a deserving award winner.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

I write about classic science fiction and occasionally fantasy; I sometimes make maps for Doom II; and I'm a contributor to the videogames site Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|