|

It’s that time again - my annual roundup of the best books I read during the year. Once again in 2022, I aimed to read 50 books and successfully hit the target; over 11,000 pages in all. This year, almost everything I read was fiction. As usual, science fiction was my main focus but I also read more fantasy than normal and a few crime novels and thrillers.

Before we get to the good stuff, what was the worst book I read in 2022? Well, I read very little that I didn’t enjoy but I was very disappointed by Forever and a Death by Donald E. Westlake. This is a novel which the revered crime author built up for a concept he had for a James Bond movie in the mid-’90s - ultimately, it was Tomorrow Never Dies which was made. Westlake’s book is overlong, drags horribly, has a ludicrous central concept and doesn’t deliver any of the necessary thrills - it’s a far cry from his best work. With that bit of business dealt with, here are the ten best books that I read in 2022.

0 Comments

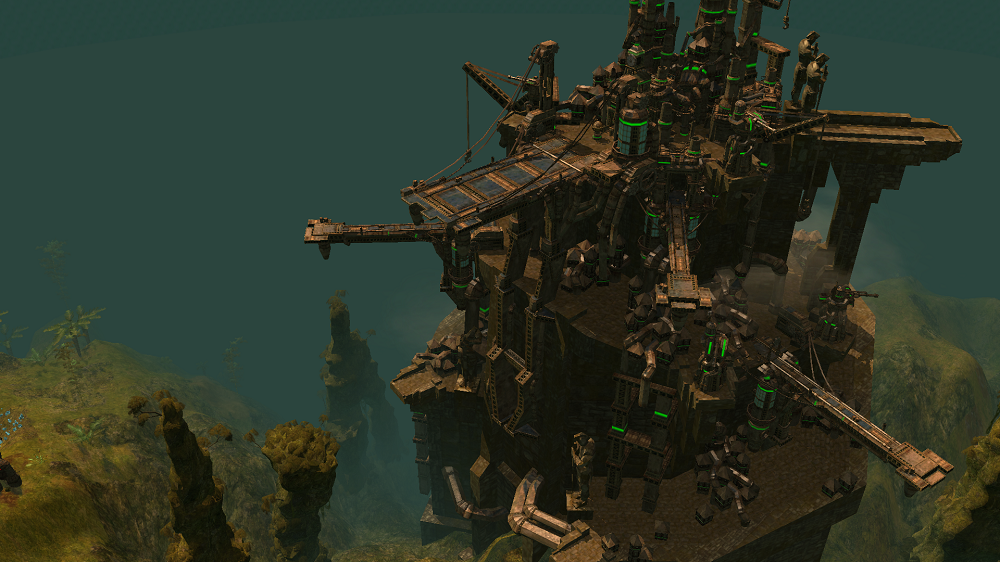

November was a month mostly dominated by retro games, as I played a mix of old favourites and titles from yesteryear that I missed at the time. I caught up with the classic stealth game Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory (2005), revisited forgotten strategy Rise of Legends (2006), and the flawed tactics of Star Trek: Away Team (2001). On the more recent side, I also continued my exploration of a long-running series, filling in a gap with Sniper Elite 4 (2017).

Despite this retro focus, I also covered some new games - including the excellent third-person action game Evil West, another product of the busy team at Flying Wild Hog. And following on from my review of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II, I also braved the battle royale battlefield of its free-to-play spinoff Warzone 2.0.

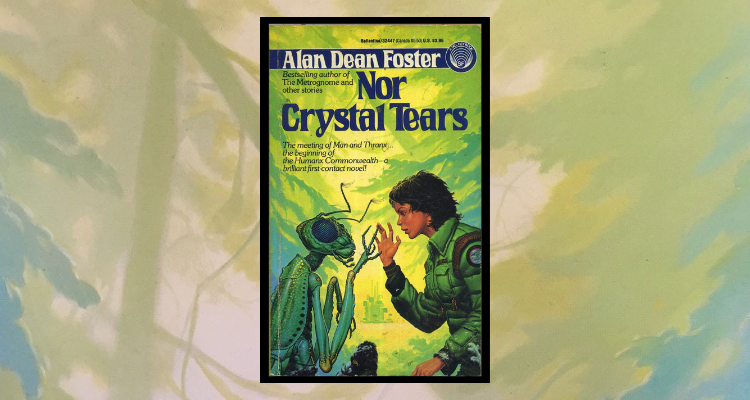

In Alan Dean Foster’s Humanx Commonwealth series of science fiction novels, a unique union between humans and the insectoid Thranx race becomes a major power in the galaxy. Two species that are so different in appearance and mentality seem destined to mistrust and fear one another - so how could they overcome these differences?

Originally published in 1982, Nor Crystal Tears is the third standalone entry in Foster’s series, and begins to answer exactly that question. Set earlier in his fictional chronology than any other story, the novel focuses on the very first contact between humans and Thranx. Unusually for a story of this type, it explores not the human perspective, but instead the alien one. The protagonist is Ryozenzuzex, a Thranx agricultural expert living on the peripheral world of Willow-Wane. While he initially seems an unlikely hero, Nor Crystal Tears explores how Ryo’s actions change the course of history.

“Science Fiction Classics” is a series of anthologies and books of republished fiction produced by the British Library and edited by Mike Ashley. Each of the anthologies focuses on a specific recurrent topic in science fiction and includes a mix of well-known and rediscovered stories.

Published in 2021, Spaceworlds collects fiction dealing with life inside space habitats of various kinds: starships, stations, generation ships, and even a “space shield”. The nine stories cover a relatively short period of science fiction history, from 1940 to 1967. Note that I have omitted one of the stories, “The Ship Who Sang” by Anne McCaffrey, because I have read it previously and did not re-read it.

October has been a huge month in the world of games, with a bevy of significant releases. The record five games I reviewed for Entertainium encompass all possible levels of budget and scale. At the indie end of the spectrum, I covered Dome Keeper and the superb retro-style shooter Cultic, which recaptures the grisly glory of Blood (1997).

At the mega-budget, tentpole release side of things, I reviewed the troubled open-world superheroism of Gotham Knights and the solid-as-ever gunplay of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II. In between these two extremes, I also played action-RPG Asterigos: Curse of the Stars, which is what some would term a “AA” game. For some reason, almost every big outlet declined to evaluate this intriguing Taiwanese Soulslike, so I was glad to give it some degree of exposure. Finally, I found time for just a couple of older games during October. I jumped on the bandwagon of Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance, which is almost ten years old but became very high-profile in 2022 because of memes - or what the game itself calls “the DNA of the soul”. I also had a great time with the single player campaign of Titanfall 2, which has also won itself cult status due to the quality of its innovative level design.

Another month bites the dust, and it was a busy one for me. Writing for Entertainium, I reviewed three games in September - a record. First up was Circus Electrique, an interesting mix of management and turn-based battles in steampunk London. I was much less impressed by No Place for Bravery, a Brazilian indie Soulslike which I found to be way wide of the mark. Conversely, I liked Sunday Gold far more than I expected to. My hatred of point-and-click adventure games is on the record, but this one won me over with its logical puzzles and the addition of its own turn-based combat.

This month’s update also features two older games. I caught up with Iron Harvest (2020), a noble effort to revitalise the ailing real-time strategy genre which meets with mixed results. And lastly for September, I finally played BioShock Infinite (2013), a full nine years after it came out. Irrational’s sequel is showing its age a bit, but it’s still easy to see why it received such a rapturous reception at the time. My take on all these games, as well as a preview of what I’ll be playing in October, is below the cut.

American writer Patricia A. McKillip, who died in May 2022, was a major author of fantasy and science fiction. She was noted for her stylised, poetic prose and for stories rich with strong themes. She wrote many novels including the Riddle-Master trilogy (1976 - 1979), but all of her books after 1994 were standalones.

McKillip’s breakthrough was her first novel for adults. The Forgotten Beasts of Eld was published in 1974, and won the first World Fantasy Award the following year. The book was written when the author was just 26, and has become a prominent classic of the genre. Notably, it is an entry in both iterations of the Fantasy Masterworks line. The book focuses on a powerful “wizard woman”, who dwells in seclusion with a group of enchanted animals held there by her magic. But how does the novel weave a spell of its own?

It’s a brief update this time around - while I played quite a bit in August, I won’t be done with some of those games until well into September. What is on the docket is a set of four very different games, in a very wide range of styles.

First up, I played the very meta French adventure There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension (2020). While it definitely hasn’t converted me to point-and-click adventure games, it’s easily the best one I’ve played. Next up is a pair of games I’ve reviewed for Entertainium. The first is Cursed to Golf (2022), which failed to impress me with its eccentric take on the sport. I much preferred the turn-based tactics of Hard West II (2022), even though I have some misgivings about its difficulty. Finally, the best gaming experience I had in August was Metro: Last Light (2013), the superbly atmospheric shooter sequel made in Ukraine and Malta by 4A Games.

Before 1972, American author Barry Malzberg had written a handful of science fiction novels and over a dozen works of erotic fiction, mostly under psuedonyms. His breakthrough came with Beyond Apollo, which won the first ever John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1973. It received a mixture of rapturous praise and scathing criticism. What made this slim volume one of the most divisive and controversial SF books of the 1970s?

This short collaborative novel, originally serialised in Analog magazine in 1975, focuses on humans and aliens trapped together in a cramped interstellar escape module. Despite a promising start, Harrison and Dickson struggle to wring much interest out of this concept.

|

About

I write about classic science fiction and occasionally fantasy; I sometimes make maps for Doom II; and I'm a contributor to the videogames site Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|