|

It’s a brief update this time around - while I played quite a bit in August, I won’t be done with some of those games until well into September. What is on the docket is a set of four very different games, in a very wide range of styles.

First up, I played the very meta French adventure There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension (2020). While it definitely hasn’t converted me to point-and-click adventure games, it’s easily the best one I’ve played. Next up is a pair of games I’ve reviewed for Entertainium. The first is Cursed to Golf (2022), which failed to impress me with its eccentric take on the sport. I much preferred the turn-based tactics of Hard West II (2022), even though I have some misgivings about its difficulty. Finally, the best gaming experience I had in August was Metro: Last Light (2013), the superbly atmospheric shooter sequel made in Ukraine and Malta by 4A Games.

0 Comments

This latest instalment of my monthly series on the games I’ve played has four entries. It kicks off with Strange Brigade and Yooka-Laylee and the Impossible Lair, two very different games which are united by their unmistakable Britishness, sense of humour, and love of alliteration. Next up I have a few words about the fairly obscure action RPG Of Orcs and Men, made across the Channel in France. If you’ve enjoyed the fantasy stealth games in the Styx series, then you may enjoy the game that first introduced that gregarious goblin.

Finally for July, I revisited an indie masterpiece which has just been given a free and impressive overhaul. Tactics classic Into the Breach has been picked up by Netflix, who are making it available to their subscribers. To celebrate, Subset Games have upgraded all versions of the game to the even more excellent Advanced Edition. This gratis update adds a ton of new features, and makes one of the best indie games ever somehow even more perfect.

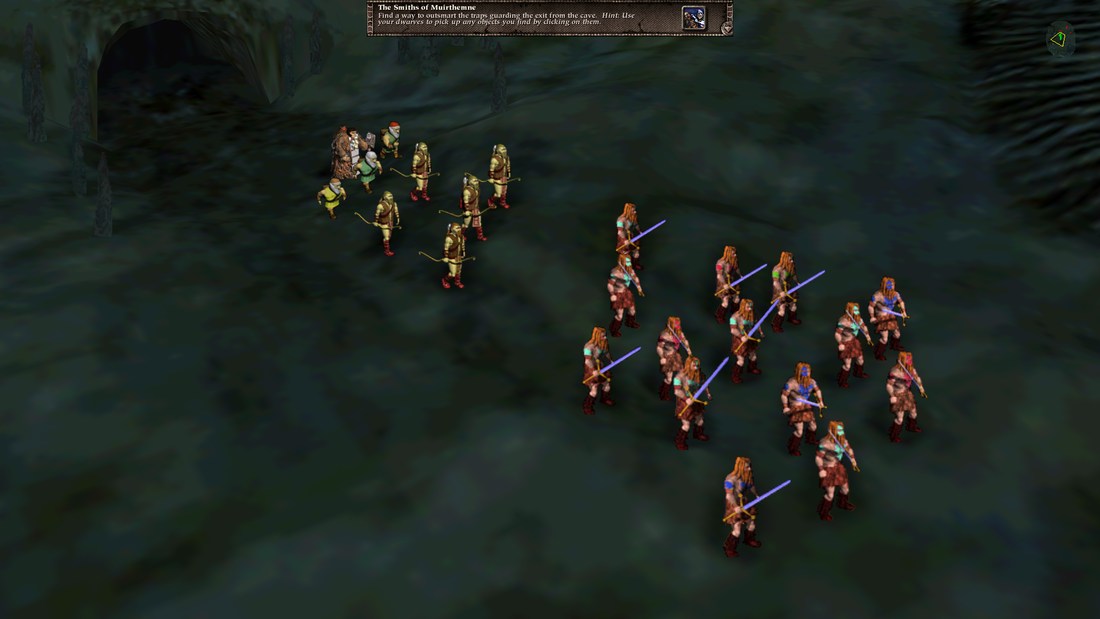

Today, developers Bungie are known for the blockbuster Halo series and more recently, for the Destiny games. And while the studio changed first-person shooters forever, first on the Mac and then on consoles, none of their later successes would have been possible without their earlier work in a different genre altogether. It was the success of pioneering real-time tactics game Myth: The Fallen Lords which, in part, prompted Microsoft to purchase Bungie and to help propel Halo to industry-shaking success in 2001.

Myth was ahead of its time. Its 3D environments were some of the first in the genre and Bungie’s work helped to forge a new style of gameplay. They cut away the base building, resource management, and large unit counts that defined Command & Conquer (1995) and Total Annihilation (1997). Myth isn’t a strategy title at all - but part of the first wave of real-time tactics games. It does more than make players think; it makes them feel. Thanks a unique union of writing and gameplay, each of Myth’s missions inspires feelings of desperation, terror, relief and - hopefully - triumph. 25 years later, it’s the emotional impact of Myth which makes it special to this day.

There’s not much need for preamble this month - I had a busy June, but still managed to play quite a few games. They were mostly on the older side; in fact the only 2022 release I played during June was a demo, and I rarely play those.

I revisited two classics from my youth which still stand up remarkably well, in the form of gloomy tactics game Myth: The Fallen Lords (1997) and the forgotten Indiana Jones and the Emperor’s Tomb (2003). I continued my increasingly familiar ramble through the Halo series with the fairly tiresome spinoff Halo 3: ODST (2009), and that demo I mentioned was for the upcoming Agent 64: Spies Never Die. The real standout for me, though, was definitely Dragon’s Dogma. Inspired by the long-awaited announcement of a sequel, I finally picked up Hideaki Itsuno’s cult favourite action RPG and have been revelling in its idiosyncratic charms.

May’s instalment of “what I played” is a relatively brief one, simply because - well, I didn’t play that many games during the month. What I did unexpectedly get the chance to do is to review the excellent Sniper Elite 5, which is easily one of my favourite games of 2022 so far. I can admit to a surge of local pride, as developers Rebellion are based just down the road from me in Oxford. My full thoughts on the game are available for your reading pleasure at Entertainium.

I of course also found a bit of time to tackle some older games. Thanks to the generous folks at Epic, I was able to play hyper-fast futuristic racer Redout (2016). I took a bloody trip into the distant past with Raven’s badly dated shooter Soldier of Fortune (2000). Finally, I have a few thoughts on the remaster of the end-of-the-world action-adventure Darksiders (2010).

For me, April was another bumper month of games. In this month’s instalment of “What I played”, I cover seven games including two brand new ones which I’ve reviewed, and even one unreleased one, all of which I covered for Entertainium. In boomer shooter Forgive Me Father I confronted eldritch abominations, cosmic horrors and a sometimes severe lack of ammunition. B.I.O.T.A., meanwhile, is a very entertaining 8-bit style side-scroller set on an asteroid plagued by ravenous mutants. Both of these games have largely flown under the radar, but I do recommend them.

The four older games I tackled in April were the impressive remake Black Mesa (2020), underrated open-world shooter Rage 2 (2019), baffling Japanese adventure Yakuza 0 (2015) and the excellent sequel Rise of the Tomb Raider (2015).

Rage 2 has been called “the sequel nobody wanted”, and with some justification. Developed by id Software and released in 2011, the original game didn’t exactly set the world on fire. Supposedly, id Software began working on a sequel which was terminated so that the company could focus on the 2016 Doom game. Later, the project was restarted under new management. The Rage 2 that saw release in May 2019 was largely developed by Swedish outfit Avalanche Studios, with the support and supervision of id Software. It also uses Avalanche’s own proprietary APEX engine.

On release, Rage 2 got the dreaded “mixed reviews”. It got a lot of 7 out of 10 scores, which in the demented world of video game scoring is generally taken to mean “this game sucks”. It’s quite possible that critics were increasingly tired of open-world games, and saw little need for a Rage sequel. The game’s structure may also have facilitated rushed playthroughs by critics, which may have kept them from seeing it at its best. Three years on, though, I’ve played Rage 2 for the first time and have been very pleasantly surprised. In fact, there’s a plausible case to be made that this broadly unwanted and unloved sequel is one of the more worthy shooters of recent years. It may have hilariously convoluted upgrade menus, and a thin story, but its core features are very entertaining indeed and it really gets a lot right. This, then, is my case in support of Rage 2 in six easy steps.

Appropriately enough given the state of the world, I start this month's games roundup with the post-apocalyptic tactics game Mutant Year Zero: Road to Eden (2018). Later in March I tapped into the cultural zeitgeist - as I always do! - by going full goblin mode in the excellent stealth game Styx: Master of Shadows (2014).

Strap in, because this month's roundup is, happily, a particularly long one. There are a total of seven games to cover, even if one is technically "just" a DLC. On Entertainium duties, I also got the chance to cover a new game I'd been looking forward to. Sadly, Weird West didn't live up to my personal expectations, but I'm aware that I'm in the minority on that front.

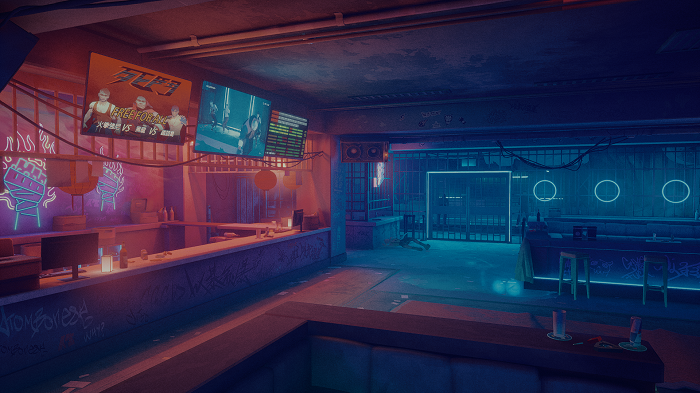

Another month, and another step in the world seemingly disintegrating in front of our eyes. February was another tough four weeks of 2022, as our stupid, cruel and cowardly leaders continued to throw ordinary people under the bus. At least, as ever, there were games to play. In recent weeks I tackled two huge older games which I hadn’t previously played. One was the $6 billion juggernaut of Grand Theft Auto V (2013), and one was the triumphant return of the Slayer, Doom Eternal (2020).

Excitingly, I also got the chance to play two brand new games in the form of martial arts brawler Sifu and the shooter sequel Shadow Warrior 3. These two Asian-themed action games were both on my list of the games I’ve been most looking forward to this year, and they both lived up to my expectations - albeit in somewhat surprising ways. A quick overview of all of these games will follow, but for my in-depth thoughts on the newcomers check out my full-length reviews published on Entertainium.

Next month marks the second anniversary of Doom Eternal, which arrived just as the COVID-19 pandemic struck. The two have in some ways have followed a similar course since then, regularly introducing new variants to keep us on our toes. Late last year I revisited Doom (2016) in anticipation, and this month I finally caught up with id Software’s frenetic shooter sequel.

It’s one of those games which obviously cost a vast sum to develop, and every cent is seen on screen and felt in the slickness and addictiveness of the gameplay. It’s also exhausting, with combat so intense and fast-paced that I only ever tackled one level per day. It’s too late for anything so grandiose as a review, and arguably too early for a retrospective so what follows is merely some scattered, personal reflections on my experience with the game. The short version is that I loved Doom Eternal, albeit with some significant caveats. |

About

I write about classic science fiction and occasionally fantasy; I sometimes make maps for Doom II; and I'm a contributor to the videogames site Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|