|

A debut novel which deals with guilt, art, and suspicious happenings on a troubled colony founded on matter transmission.

Originally published in 1992 - and out of print for many years - Meridian Days is the debut novel by British SF author Eric Brown (1960 - 2023). Following on from a string of successful stories, the novel is connected to Brown’s wider “Telemass” setting. Meridian is a planet over 20 lightyears from Earth, which orbits the star Beta Hydri. Its colonisation by humans has been made possible by advanced technology; a huge sunshield which dampens the star’s intensity, and an interstellar matter transmission system which permits trade with distant Earth. The novel’s protagonist is Bob Benedict, a former spacecraft pilot with a drug habit, a guilty conscience, and a desire for solitude. Slowly but surely, Benedict is drawn into the tangled affairs of a prominent artist, Tamara Trevellion, and her troubled family. The former pilot becomes determined to establish the facts of a case which may have dramatic implications for the future of Meridian itself.

0 Comments

The landmark novel from the Northern Irish writer combines his interest in optics with an anti-neutrino planet and an unusual African setting.

Originally published in 1976, A Wreath of Stars is a standalone science fiction novel and the ninth to be published by Northern Irish author Bob Shaw (1931 - 1996). Set in the near future, the story is a chain of events triggered by the invention of a groundbreaking new kind of lens. This makes possible the discovery of a previously unknown type of planet, one which is hurtling towards Earth. Fortunately, “Thornton’s Planet” is composed of anti-neutrinos. Being insubstantial, it poses no threat. Some time after the initial panic subsides, ghost sightings are reported in the depths of a diamond mine in East Africa. Something links these strange occurrences, and humanity’s view of its place in the universe is about to be challenged like never before. A Wreath of Stars is a brisk, exciting SF novel in the dependable tradition of the 1970s. While its scientific backdrop is dubious - especially today - Shaw weaves the sciences of optics and astronomy, alien life, and Earthly conflict into a compelling tale.

The definitive arcology novel is an urban story with grim politics, skilfully told.

Larry Niven (1938 - ) and Jerry Pournelle (1933 - 2017) made up one of the most fruitful collaborative teams in 1970s and 1980s American SF. Beginning with The Mote in God’s Eye (1974) - which was nominated for the Hugo, Locus, and Nebula Awards - they delivered a string of successful novels. They were united in their enthusiasm for hard SF approaches and in their staunch right-wing, libertarian political views, and worked together over a period of more than 30 years. Oath of Fealty is the fourth Niven-Pournelle collaboration, published initially by the small Phantasia Press in 1981. It is one of the last entries in David Pringle’s book Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels (1985) and James Wallace Harris included it in his list of the defining science fiction novels of the 1980s. A standalone science fiction novel, Oath of Fealty is a key exploration of the concept of an arcology, an example of the wider keep trope in SF. In near-future California, Los Angeles is in the grip of poverty and crime. A private walled city-state, Todos Santos (or “All Saints”), is constructed over the ruins of a burned-out part of LA. Oath of Fealty explores the workings of this new kind of community, in which residents trade privacy for security. A break-in is the inciting incident for a new conflict between Todos Santos and the city of Los Angeles. Involving ecology activism, betrayal, private security, chemical weapons, and a kind of propaganda war, this struggle will determine whether the walled community can survive. While somewhat dated and suffused with harsh right-wing views that many will find objectionable, Oath of Fealty is a brisk and cleverly constructed take on the future.

A classic robot novel with a philosophical bent, set in a far-future world.

In a rural backwater, a master robot-maker and his wife construct a robot of their own. “We made you”, they say to him when he awakens, “you are our son.” The robot, Jasperodus, laughs at them dismissively and immediately walks out of their lives. He embarks on a series of adventures, all of them affected by his particular quirk - uniquely among machines, he has full consciousness: a soul. Originally published by Doubleday in 1974, The Soul of the Robot is the sixth novel by Barrington J. Bayley. Today, it is the best-known novel by this under-recognised author. It hews to Bayley’s frequent approach in that it fuses a fast-moving, pulpy story with deeper speculations. Jasperodus imposes himself excitingly on a far-future world of fractured empires and decayed technology; but also explores the riddle of consciousness, where it comes from and what it means to be alive.

A swashbuckling classic of elevated pulp, steeped in Einstein’s physics and the historical theories of Arnold J. Toynbee.

Born in Texas, Charles L. Harness (1915 - 2005) had an unusual, stop-start career in science fiction. During the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s he published just one novel per decade while also working as a patent lawyer. He is described by the science fiction encyclopedia (SFE) as a victim of “relative neglect”, and his work was quite unrecognised until towards the end of his life. However, Harness’ first novel The Paradox Men has earned some degree of fame, often due to its fond reception in the UK. It was praised in an introduction by Brian Aldiss, and it is included in David Pringle’s landmark book Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels. There, it is memorably described as “one of the shlock classics of US magazine SF”. The Paradox Men is a dizzyingly fast-moving example of elevated pulp, called “shamelessly melodramatic” by the SFE and packed full of outrageous ideas, outlandish plot devices, and swordfights in outer space.

Delving into the mysteries of Jupiter with two stories which link two generations of the UK's greatest science fiction writers.

An enduring icon of science fiction, Arthur C. Clarke (1917 - 2008) is best remembered for his novels, especially Childhood’s End (1953), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Rendezvous with Rama (1973). However, up until around 1962 he was also a prolific writer of short fiction. He published so much, in fact, that the most comprehensive collection runs to over 900 pages, or an intimidating 50 hours in audiobook form. Originally published in the December 1971 issue of Playboy, “A Meeting With Medusa” is generally thought of as Clarke’s last significant shorter work. Notably, it won the Nebula Award for Best Novella the following year. It was also an early inspiration for two of Clarke’s successors in the British SF scene. 45 years after the novella’s publication, Stephen Baxter and Alastair Reynolds delivered their novel-length sequel, The Medusa Chronicles. Taken together, these two works form an exciting exploration of the possibility of life on Jupiter, the effects of transhumanism, and the relationship between humans and machines. They are also a fascinating link between two generations of British science fiction talent.

A genuinely harrowing and yet moving novel of an unstoppable assault on Earth by unknowable aliens.

Planet Earth has had some rough times in science fiction. Over the decades, writers have had it besieged, invaded, conquered, frozen, incinerated, and even stolen. Of course some stories have gone all the way and destroyed the Earth altogether. There are many ways to approach this narratively; in the British comics series Shakara, our world is glibly destroyed on the first page, followed shortly by the last surviving human. In The Forge of God (1987), the Earth’s demise is an inevitability. Greg Bear’s novel of apocalypse was published when he was establishing himself as a leader of American hard SF in the 1980s. This is a sophisticated, chillingly believable, and scientifically rigorous view of the end of the world. Crucially, Bear is as interested in human beings as he is in the devastation that unfolds. Knowing the outcome does not undermine the emotive power of his human-scale story. While humankind makes a stab at self-preservation, this novel confronts the chilling idea of a broadly hostile universe for which Earth is woefully unprepared. In a way, though, The Forge of God is oddly uplifting - dealing as it does with the vanishing beauty of our world and that sturdy cliché, the strength of the human spirit.

A key novel in its author’s development is set in a world where a new religion could pave the way for humanity’s expansion to the stars.

Many science fiction authors have crafted one or more “future histories”, which trace humanity’s imagined development in the years to come. The product of a somewhat unusual writing and editing process, To Open the Sky was the first true future history written by the prolific American author Robert Silverberg. In this distinctive take on the idea, the journey beyond Earth’s solar system rests less on technology, and much more on religious belief. In the 1950s, Silverberg was working at “assembly-line speed”, producing many competent SF stories for several magazines. Later, he entered a new phase in which he remained prolific but became more thoughtful and strategic in his approach. To Open the Sky is one of the novels which commenced the most praised part of his career, from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. It is a brisk projection of humanity’s future, steeped in the theme of religion and cleverly bringing together five carefully planned, previously published stories. A Thousand Worlds: Dying of the Light (1977) and Tuf Voyaging (1986) by George R.R. Martin5/16/2024

A look at the only two full-length works in the Thousand Worlds science fiction setting by the author of A Game of Thrones.

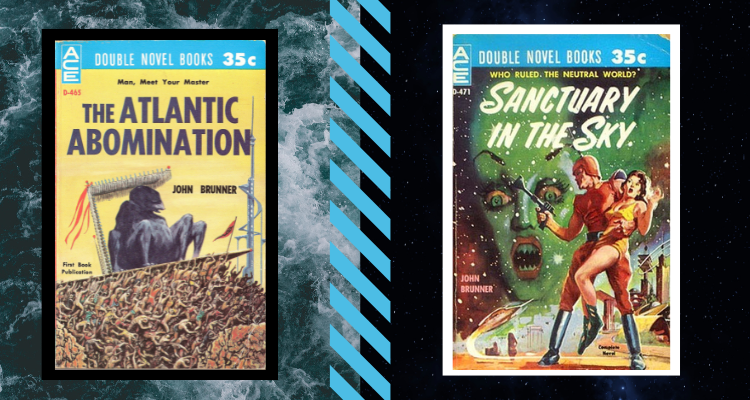

Few science fiction and fantasy writers can really be thought of as household names, but George R.R. Martin definitely qualifies. His as-yet unfinished epic fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire, has sold over 90 million copies and its TV adaptation was an international phenomenon in its own right. Martin has been called “the American Tolkien”, and is almost synonymous with the fantasy genre. What even some of his fans may not realise, though, is that Martin was originally successful in the field of science fiction. Between 1971 and 1986, Martin published 26 shorter works of SF which all formed a part of a single setting, which he called the “Thousand Worlds”. In this loose future history, humans have achieved interstellar travel and have colonised numerous planets. However, due to the vast distances involved and the impact of conflict, humanity has splintered into various disparate cultures. Many of the stories explore the differences between these societies, as well as with other forms of life. They range quite widely in style, from the military SF of “The Hero” (1971) to the horror of the novella Nightflyers (1980). Here, we explore the only two full-length works in the Thousand Worlds setting. The first is the novel Dying of the Light (1977), Martin’s debut novel set on the declining rogue world of Worlorn. The second is Tuf Voyaging (1986), a collection of stories featuring the eccentric trader Haviland Tuf. Together, they are an interesting insight into the neglected SF works of an author who would become a dominant force in fantasy. A pair of Aces: The Atlantic Abomination (1960) and Sanctuary in the Sky (1960) by John Brunner5/7/2024

Two early novels released as part of Ace Doubles in 1960 show a different side to the UK's first winner of the Hugo Award for Best Novel.

Today, John Brunner (1934 - 1995) is best known for his four lengthy, unsettling, and prophetic “tract novels” published between 1968 and 1975. These were written during a period when he consciously elevated his ambition, and sought to grapple with the issues facing the world in the second half of the 20th century. The novels were critically successful. Most famously, the incredibly ambitious story of overpopulation Stand on Zanzibar made Brunner the first British winner of the Hugo Award for Best Novel. However, these novels were not lucrative and “they in no way made Brunner’s fortune.” But Brunner’s work cannot be reduced to four novels. In his heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, he was extremely prolific. Notably, in the six years from 1959 he published a massive 27 novels through Ace Books alone. Many of these formed one half of the US publisher’s famous “Ace Doubles”, which comprised two short novels printed back-to-back in the dos-á-dos or tête-bêche format. In books like these, Brunner’s works were paired with stories by authors like Poul Anderson, Philip K. Dick, and Samuel R. Delany. This is a look at two of the four short novels which Brunner contributed to Ace Doubles during one year, 1960. The Atlantic Abomination and Sanctuary in the Sky are described by the Science Fiction Encyclopedia as “are typical of the storytelling enjoyment he was able to create by applying to ‘modest’ goals the formidable craft he had developed.” |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|