|

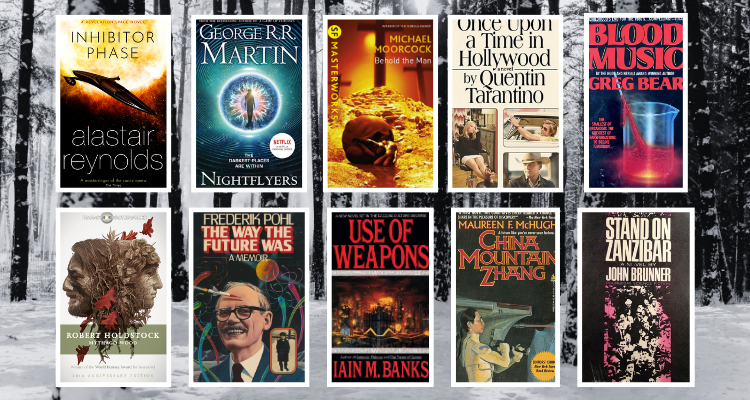

2023 has been another fascinating year of reading for me. Once again, I set out to read 50 books and once again, my main focus has been on science fiction. This year, seven of my top ten are science fiction novels; one is a non-fiction book by an SF author, one is the fantasy novel Mythago Wood (1984), and one (surprisingly) is by one Quentin Tarantino. I strongly recommend all of these books - if you’ve read them, and have thoughts about them, I’d be interested to hear from you in the comments below.

0 Comments

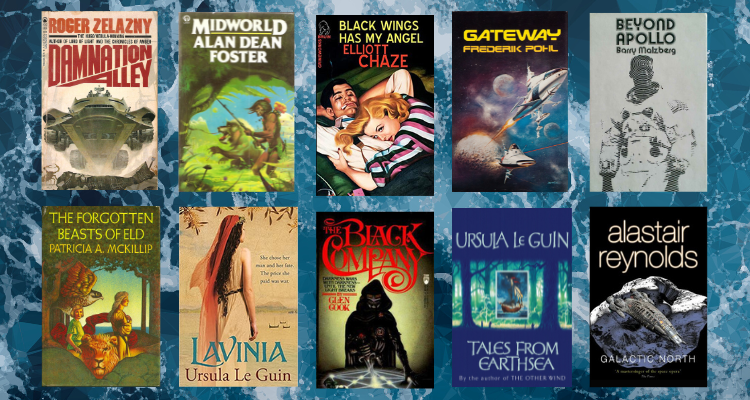

It’s that time again - my annual roundup of the best books I read during the year. Once again in 2022, I aimed to read 50 books and successfully hit the target; over 11,000 pages in all. This year, almost everything I read was fiction. As usual, science fiction was my main focus but I also read more fantasy than normal and a few crime novels and thrillers.

Before we get to the good stuff, what was the worst book I read in 2022? Well, I read very little that I didn’t enjoy but I was very disappointed by Forever and a Death by Donald E. Westlake. This is a novel which the revered crime author built up for a concept he had for a James Bond movie in the mid-’90s - ultimately, it was Tomorrow Never Dies which was made. Westlake’s book is overlong, drags horribly, has a ludicrous central concept and doesn’t deliver any of the necessary thrills - it’s a far cry from his best work. With that bit of business dealt with, here are the ten best books that I read in 2022.

Just recently, I’ve become an avid reader of Paperback Warrior. It’s an invaluable website focused on the pulpy paperback fiction of the 20th century, with a strong emphasis on crime noir, spy thrillers, men’s action-adventure, and Westerns. The website, and its accompanying podcast, are a brilliant window into a fascinating era of fiction, much of it aimed at blue-collar working men in the United States.

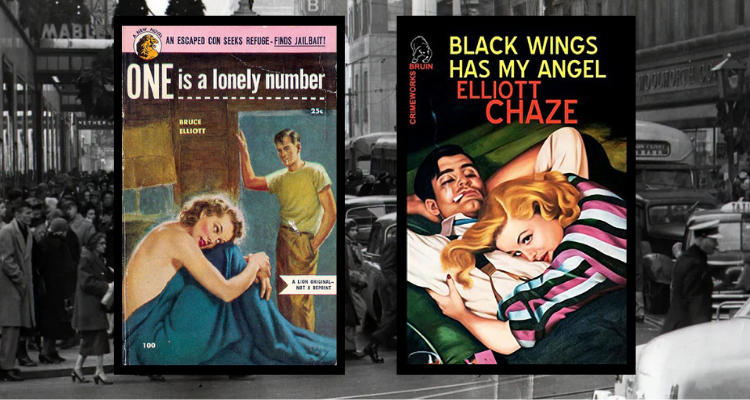

The site’s authors are paperback archaeologists of the first rank and their thousands of reviews are always concise and informative. While much of my reading is classic science fiction, Paperback Warrior has recently been my guide into the often brilliantly dark crime fiction of the same era. What follows is my layperson’s reviews of two novels strongly recommended on the site, and which can be found together in a great value ebook available from California-based Stark House Press. One is a Lonely Number (1952) by Bruce Elliott is a real obscurity, a dark and nihilistic escaped-convict story set mostly in Ohio. Black Wings Has My Angel (1953) by Elliott Chaze is one of the most praised crime noir books of its era, and for many years was a very desirable rarity in paperback. These are both excellent books, terse and powerful and as lively today as they were in the early ‘50s. If you like the sound of them, then I can only again recommend Paperback Warrior and Stark House Press, who I’m sure will guide you and I alike to many more engaging reads from back in the glory days of paperback fiction.

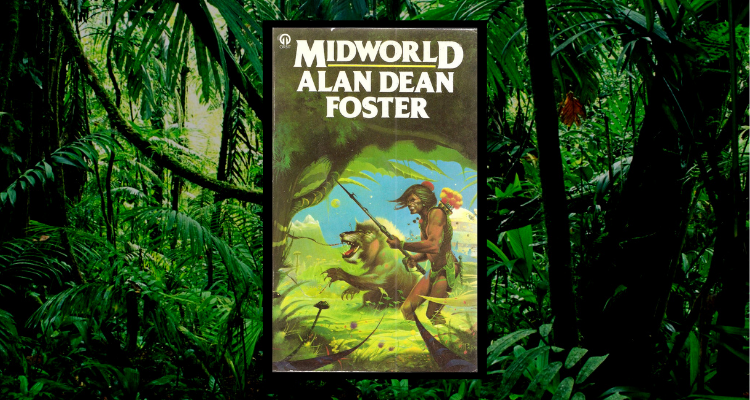

Quentin Tarantino once called Alan Dean Foster “the king of movie novelisations”, and it’s a fair description. Most famously, Foster wrote the first ever Star Wars novel, a novelisation of the original film which was released much earlier than the big screen version, in November 1976. Later, Foster would novelise other important science fiction movies, including Alien (1979) and its first two sequels, Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), Outland (1981), The Thing (1982), and Starman (1984). While novelisations are often thought of as one of the most low-brow forms of writing, Foster elevated the genre with his strong SF background and ability to expand upon scripts with additional detail.

However, Foster has done far more in his long career than merely re-work scripts into books. He has a very extensive catalogue of SF works under his belt, most notably in his “Humanx Commonwealth” universe, which centres on an alliance between humans and the intelligent insectoid species the Thranx. Midworld, published in 1975, is a superb standalone novel in this setting - albeit one which doesn’t feature the Thranx. Instead, it is set on a nameless, verdant, and hostile jungle planet which is home to the descendants of humans left stranded by a starship crash many decades earlier. In the book, Foster tells an enthralling story within a brilliantly realised and convincing setting. This is an SF novel which will particularly appeal to those who enjoy stories rooted in biology and ecology, and it was a very clear influence on James Cameron’s megahit movie Avatar (2009). Stick around to the end to get more information on this intriguing connection. In the meantime, this review covers what makes Midworld so special, and such a good entry point into Foster’s body of work.

Fiction is full of a whole variety of apocalyptic scenarios - like the dead rising from the grave, a full-blown nuclear exchange, or a takeover by hostile machines. There is one scenario that has what you might call an “advantage” over these ones, though. The catastrophic collision of an asteroid into the Earth is all the more unsettling because it has actually happened before, and - looked at over a sufficiently long timescale - will inevitably happen again. It’s perhaps the ultimate disaster that we can imagine, and yet it is also very real.

According to the dominant Alvarez hypothesis, the dinosaurs and most of the planet’s species were wiped out 66 million years ago by the impact of an asteroid estimated to be between 10 and 15 kilometres across. That’s roughly the same size as Phobos, one of the moons of Mars. The strike would have had an explosive force equivalent to 100 million megatonnes of TNT; that’s the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, multipied by a billion. There are many other large craters around the world, each of which is the legacy of a devastating impact in the distant past. These include the Karakul crater in Tajikistan, the Popigai crater in Russia and the Vredefort crater in South Africa, the world’s biggest at over 160km across. The asteroid impact scenario has inspired many works of fiction including last year’s film Don’t Look Up, the duelling 1998 blockbusters Deep Impact and Armageddon, and numerous sci-fi stories and novels. Of these, one of the most notable is the book The Hammer of God, written by Arthur C. Clarke and published in 1993. Taking into account the latest science of the time, the book was the second-to-last novel that Clarke wrote alone and the last one he wrote alone outside of the Odyssey series. Incorporating elements and styles from his better known earlier books, The Hammer of God partly inspired Deep Impact and could be a good entry point for newcomers to Clarke’s body of work.

Way back in September 2020, I began reading and writing about the Hainish “cycle” of SF novels by Ursula K. Le Guin (1929 - 2018). It has taken a year and a half, but the time has now come for my reflections on the eighth and final Hainish book, The Telling, which was published in 2000.

The Hainish books began with Le Guin’s very first novel Rocannon's World in 1966. The various books and short stories share a loose continuity and are set over a large span of time. They are predicated on the idea that humans evolved not on Earth, but rather on the fictional planet Hain. In the stories, an interstellar association called the “League of Worlds” or later the “Ekumen”, gradually reunites various human-like peoples who live on a number of planets including Earth. This concept is central to some of the stories, and barely mentioned in others. The Telling is a fairly short novel which revisits several of the themes which Le Guin had previously explored in the earlier Hainish books. In this sense, it makes for a fitting conclusion to the loose series. Opinions are divided on where to start with the Hainish stories, but I would certainly caution against starting with The Telling; while its setting and characters are entirely new, it leans heavily on previous depictions of the Hainish people and of the Ekumen. While this is generally felt to be one of the more minor entries in the series, The Telling has all the deep engagement with ideas that Le Guin fans will expect by this point.

Mars. The “red planet” has had a powerful presence in the human imagination for thousands of years. Because it is visible with the naked eye, and because of its striking colour, Mars has been directly observed by countless people. It has worked its way into mythology, religion, scientific inquiry, and of course into science fiction. From the lurid alien world of the Victorian and pulp eras, to the more grounded portrayals that followed the visit by Mariner 4 in the 1960s, to the contemporary realistic approach, Mars has been a staple of SF.

In particular, the idea of colonising Mars has fascinated writers for generations. Because of the planet’s relative closeness to Earth, the presence of its atmosphere, and the existence of water ice on the surface, colonisation by humans has long been a tantalisingly plausible prospect. Since the findings about the red planet provided by the Mariner and Viking spacecraft, depictions of human colonies in SF took on a more realistic and scientifically-grounded approach. Of these works, the epic Mars trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson is arguably the best known and most acclaimed.

It’s time for my annual round-up of the best books I read during the year. As in 2019 and 2020, I aimed to read 50 books and managed to do so. Once again I primarily read sci-fi, which is reflected in my top ten choices. However, one horror novella and a classic crime novel also crept into the list. Note that the list is in no particular order; I’d strongly recommend any of these books and a number of them have introduced new authors for me to explore further in 2022, which I fervently hope will be an actually good year for once.

As an aside, you might be interest in what the worst book I read in 2021 was. Well, this was not a close run thing. By far the worst book I read was Dragonflight (1968) by Anne McCaffrey. Now I know that the Pern series is quite popular, and no disrespect to its fans, but the first novel had me slogging through it for almost a month. Let it be put on record that for me, space fungus is an incredibly uninteresting “threat”, and that McCaffrey’s time-travelling dragons are the most lazily convenient deus ex machina I have ever encountered in a work of fiction. It’s not a series I’ll be returning to. With that out of the way, the rundown of my top books of 2021 begins with...

How will the world end? It’s a question that has occupied the minds of many SF writers over the years, but few have become as closely associated with it as John Wyndham.

Born John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris, the man who would become better known as John Wyndham came to fame relatively late in life. While he had published stories as far back as the 1930s, he finally broke through with his novel The Day of the Triffids, published in 1951 when he was 48 years old. Set in a world where a mass outbreak of blindness leaves humans at the mercy of deadly, walking plants, the book established Wyndham as a kind of prophet of doom. He would return to the theme of catastrophic events and societal collapse several times before he died in 1969. While they were heavily influenced by emerging events at the time he was writing, the best of Wyndham’s novels have an uncomfortable power even now. First published in 1953 and named for a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Kraken Wakes is one of those books. It is a story, in part, about social and political systems lapsing into a lethal paralysis just when they are needed most. In a world ravaged by a pandemic, economic shocks and climate breakdown, this is a novel which may be more relevant now than ever before.

Following the publication of The Dispossessed (1974), Ursula K. Le Guin ceased to write new stories in her Hainish universe. In the following years, she wrote some of the books which are less well known today, including the Orsinia books and the experimental Always Coming Home (1985). At the time it must have seemed as if Le Guin was finished with the Hainish cycle - but after a 16-year break, she began to publish new short stories in 1990. Eventually, she followed these up with one of the most structurally unusual books in the Hainish series - Four Ways to Forgiveness.

Rather than a novel, Four Ways to Forgiveness takes the form of four shorter works. Depending on your definition, these might be termed short stories, novelettes, or novellas. While each is broadly separate and were originally published separately, they are all set on Werel and Yeowe, two worlds in the same planetary system with a complex, evolving, and painful history. The four tales each focus on a different main character, who in their own way confronts or experiences that history first-hand. While Le Guin’s work is almost always very serious in tone, Four Ways to Forgiveness is particularly so, as it emphasises the challenging subjects of freedom, slavery, trauma, and revolution. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|