|

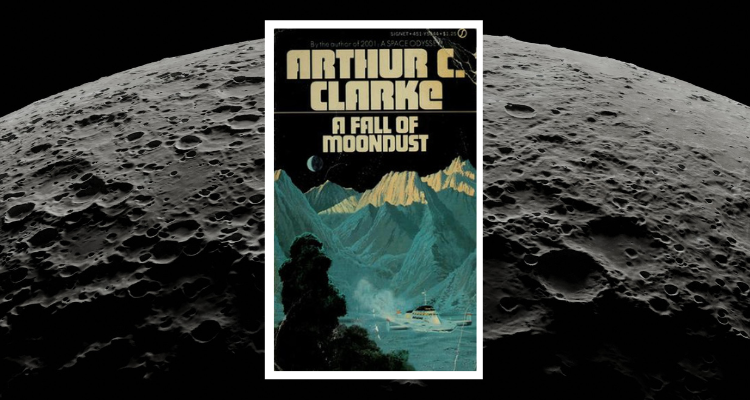

Arthur C. Clarke was very much interested in the moon. In his most famous book and its film version, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the moon is the setting for a brief but crucial sequence - the discovery of the first monolith. The moon is also a setting in Clarke’s early novels Prelude to Space (1951), Earthlight (1955) and today’s subject, A Fall of Moondust (1961). This particular book is a good example of Clarke’s approach to so-called “hard science fiction”, which strongly emphasises scientific accuracy and plausibility. Clarke crafts a story, set entirely on the moon, which uses the contemporary scientific knowledge of the time.

As it turned out, the central premise of A Fall of Moondust was invalidated just a few years after the book was published. The plot is predicated on the idea that there are areas of the moon where dust is so fine, that it flows like a liquid. This concept is used as the springboard for a tense rescue story - but when the crew of the Apollo 11 mission walked on the moon in July 1969, the theory was disproved. As Clarke points out in his introduction to the 1987 edition of his book, “the Apollo astronauts found it difficult and exhausting work to drive their core-sampler tubes into [the moon] for more than a few centimetres.” Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were certainly in no danger of sinking into the dust of the moon. The premise of A Fall of Moondust may not have survived the tide of scientific discovery, but the book has stood the test of time.

A Fall of Moondust is set in an optimistic future, in the 21st century. The world seems to be at peace, technology has transformed and continues to transform human lives, and people are gradually exploring the solar system. This kind of setting is common to most of Clarke’s books, even though they are not set in an actual shared continuity. In this case, the moon has been inhabited for some time and a small-scale tourist industry has sprung up. The main highlight of any visit is a trip across the (fictional) “Sea of Thirst”, a part of the (real) Sinus Roris. This is achieved using a unique “dust-cruiser” named Selene, which skims across the top of the choking dust bowl. Essentially, it’s a high-tech bus, providing a kind of Magical Mystery Tour to wealthy space-tourists.

Disaster strikes when energies stored up within the moon for millennia are unleashed in the form of a modest “moonquake”. This disturbance shakes up the Sea of Thirst and plunges Selene, its crew and passengers deep into the dust. The dust-cruiser cannot escape under its own power, and is equipped for mere day-trips, not for extended periods trapped under the dust. Worse, the dust settles above the craft and renders it completely invisible. It isn’t long before the Selene is noticed to be missing, and the lunar authorities begin to plan a rescue - but first, they have to find the cruiser and even that could take longer than the oxygen on board will last… The Selene’s fate is a classic disaster scenario. The challenges faced by both the craft’s unfortunate prisoners, and by the people on the surface trying to rescue them, are the core of the story. Each time a problem is resolved, granting the characters a reprieve, they encounter another potentially deadly hazard. Each of these crises is used by Clarke to explore the science of trying to survive in the unique conditions of Earth’s moon. He deals with the effects of oxygen deprivation, the perils of boredom, the need to track a heat signature, the difficulty of transporting heavy equipment, and the odd mechanics of super-fine dust. The tension is sustained right until the end, and Clarke proves that even hard SF can be written as a kind of thriller. There are some clear signs of the book’s origin in 1960, and not just its dated ideas about the nature of moon dust. The first thing the passengers do when they become stranded is to form an “entertainments committee”, which is an amusing detail. More seriously there is some relatively sexist content in Clarke’s portrayal of women on board Selene (although it’s easy to find much worse in SF of this period). Conversely, Clarke includes a sympathetic Aboriginal Australian character who talks to the Selene’s captain, Pat Harris, about the appalling treatment of his ancestors. Harris struggles to respond to this, as it turns out that he has very little awareness of Earth’s history at all. A Fall of Moondust isn’t one of Clarke’s best novels, and Earthlight is arguably a stronger moon novel in his bibliography. However, it is a book of sustained tension with an interesting scientific backdrop. It’s also true that Clarke’s writing style feels much more fresh and readable today than that of many of his contemporaries and A Fall of Moondust is a good example. If you need some light reading to pass the time on the way to your next lunar trip, this classic book is a good choice.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|