|

Legendary British author Michael Moorcock has a dizzyingly massive bibliography. He has written so many fantasy, science fiction and literary novels that surely only a handful of people can possibly have read them all. In the sphere of short fiction, though, Moorcock has been a bit less prolific. Reading his collected short fiction is the kind of undertaking that could even be completed in a normal human lifespan.

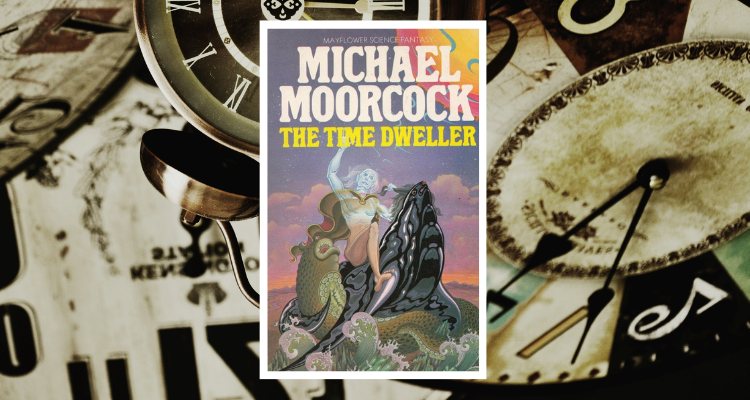

Normal human lives are in short supply, though, in The Time Dweller. Originally published in 1969, this collection is one of the earliest efforts to gather together some of Moorcock’s shorter stories. Of the nine entries in this volume, seven were originally published in New Worlds, one of the leading British SF magazines. It might not have been too difficult to get them published, because at the time the editor was one Michael Moorcock. The nine stories fit the New Wave style which the magazine was known for during Moorcock’s first tenure as editor (1964 - 1971). They are experimental, somewhat literary, and tend to involve surreal journeys or transformations of one kind or another. As with much of the author’s work, they often straddle the line between SF and fantasy. They’re also quite gloomy in tone, dealing with desperate characters striving in dying worlds. While unlike the slightly more easygoing antiheroic fantasy of Moorcock’s Elric saga, these stories are worth seeking out for fans of the author - if not so much for more casual readers.

The book opens with “The Time Dweller” and “Escape From Evening”, a pair of related stories which are both based in a sort of “Dying Earth” setting. Named for the famous 1950 collection by Jack Vance, this subgenre focuses on future versions of Earth which are exhausted, decaying, and often barely able to support human life. In this case, the world is a backward, salt-caked ruin in which giant slugs called “oozes” are thought to be well on their way to becoming the dominant species. Humans, for their part, are few in number and have lost much of their knowledge. If they travel at all outside of their low-tech conurbations, they do so on the back of strange seal-like beasts.

Moorcock’s description of the wasted future Earth is quite memorable: “Dusk had come to the universe, albeit the small universe inhabited by man. The sun of Earth had dimmed, the moon had retreated and salt clogged the sluggish oceans, filled the rivers that toiled slowly between white, crystalline banks, beneath darkened, moody skies that slumbered in eternal evening.”

In the first story, a wanderer stumbles into a town where the residents obsessively base their society around precise observations of clocks. Threatened with imprisonment for eating at the wrong time of day, the protagonist discovers he can seemingly will himself to travel in time. In “Escape from Evening”, a new protagonist travels from the moon to Earth but finds that its people are resigned to their own extinction.

Really a novelette rather than a short story, “The Deep Fix” is the longest piece in the collection and also one of the earliest, from 1963. It was not published in New Worlds, but rather in its sister publication Science Fantasy, which was edited by John Carnell (1912 - 1972). In a nightmarish future, Professor Lee. W Seward is seemingly the only sane survivor in a world devastated by mass psychosis. He attempts to build a machine, a “tranquilomat”, to pacify the hordes but is instead drawn into a bizarre dreamscape where he is menaced by the enigmatic “Man Without a Navel” and his various henchmen. The story is quite overlong, but has its moments - essentially a surrealistic take on Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954). Moorcock’s first ever novel was finished in 1958, but not submitted to publishers and only rediscovered in full in the late 1970s. In 1965, a small fragment of it was published under the same title: “The Golden Barge”. In it, restless wanderer Jephaim Tallow pursues the mysterious ship of the title without ever really knowing what it contains. Moorcock described the story as a “simple allegory”, with the river representing time and the barge standing in for “what mankind is always seeking outside itself”. Published under the pen name James Colvin in 1966, “Wolf” is one of the book’s shortest and most oblique stories. Written in the first person, it concerns a man who wants to know who “owns” a town that he stumbles into, and has a deadly encounter with a woman who seeks to help him. Also from 1966, “The Ruins” is a particularly dreamlike and metaphysical story about a man exploring seemingly endless and unearthly ruins, which are nevertheless interspersed with pockets of apparent normality. “Consuming Passion” is arguably the best story in The Time Dweller. It’s also the most grounded in a recognisable reality - South London in the contemporary 20th century. The protagonist is a pyromaniac and arsonist with a kind of god complex. His discovery that he can cause objects to combust using only the power of his mind takes his arson to a new level. In “The Pleasure Garden of Felipe Sagittarius”, a bizarre mix of historical figures including Otto von Bismarck, Adolf Hitler, Albert Einstein and Eva Braun are drawn together by a murder mystery involving possibly sentient plants. Unusually, Moorcock revised this story more than once, connecting it to his wider “multiverse”. In one instance, he replaces the main character with Seaton Begg, his own alternate version of the pulp hero Sexton Blake. The collection closes with “The Mountain”, which further underscores the bleak theme that permeates much of the book. In the story, two men wander Scandinavian wilderness where they have survived a nuclear exchange which has seemingly all but ended the human race. As dark as this concept is, it retains a dreamlike quality which is also typical of the volume. One of the two men focuses not on his own impending death, but rather on the peace and beauty of the world around him, and how it will live on after people are gone. That sentiment is about as upbeat as Moorcock gets in The Time Dweller.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|