|

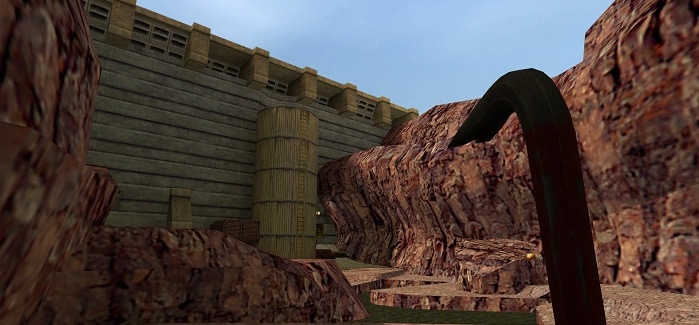

While I came to Half-Life late, Valve's 1998 masterpiece was the game that cemented my enthusiasm for games generally, and first-person shooters specifically. Replaying it almost 20 years on from its release, one aspect shines more than any other: the game's unique environments and crucial sense of place. During the early history of the FPS, developers did not tend to prioritise settings. In classics of the form like Doom (1993), Hexen (1994) and Duke Nukem 3D (1996), settings and locations were only nominal, with little to no coherence between levels or episodes. Things began to change with id Software's Quake II (1997), in which the player progressed through numerous areas of an enemy planet, Stroggos. It was Valve and Half-Life, however, which gave the FPS its first - and perhaps best - coherent sense of place. Based on technology licensed from id, Half-Life has a minimalist story drawn from sci-fi B-movies and the works of Stephen King (particularly his 1980 novella The Mist). Its main setting is the Black Mesa Research Facility, a vast US government lab complex in the New Mexico desert. When the base becomes the focal point of an interdimensional alien invasion, then a brutal US military cover-up, the player - as bespectacled physicist Gordon Freeman - must somehow find a way to bring the crisis to a close. To less innovative developers, Black Mesa would have been an ideal excuse to create the environments for which the FPS was best known - endless, identikit corridors. While inexperienced and not taken at all seriously by the likes of id Software, Valve had far grander ambitions. The Black Mesa they created is thrillingly diverse and convincing, and one of the most enduring videogame environments ever made. To be sure, there are the expected gleaming labs filled with beeping equipment - but there is also a satellite launch facility, an extensive disused rail system, parched deserts on the surface, office complexes, a waste disposal zone, and a storage area for decomissioned ballistic missiles. All this is to say nothing of the extra areas explored in the expansion packs Opposing Force and Blue Shift. Half-Life is well-known for the player's unbroken experience, in which every moment is viewed through Freeman's eyes. What is less discussed is the remarkable environmental coherence of the player's experience. Black Mesa needed to be not a series of compartmentalised levels but an actual setting, a place, in a sense no developer had really attempted before. While some of the transitions seem a bit abrupt today, Valve were tremendously successful in achieving this. Because Half-Life features little in the way of characters or dialogue, Black Mesa's environments have a dominant role in the way the game's story is told. For example, during the early part of the game the player is driven by the need to find a way to reach the surface. A clanking lift finally provides a route - but the area above is subjected to a military airstrike, and Freeman is forced back into the darkness. The grim, abandoned zones he explores next reflect the apparent hopelessness of his situation, Later, the bizarrely disjointed environments on the alien world of Xen underscore the cosmic nature of Freeman's mission: he is no longer a desperate scientist but humankind's only hope. Many of Half-Life's innovations were not learned by other developers after 1998, and this groundbreaking approach to environmental design is one of them. For example, F.E.A.R. (2005) consists almost entirely of dull industrial settings with a flat colour scheme. Unable to replicate Valve's novel transitions, Monolith Productions repeatedly used helicopter crashes to insert the player into new environments, to the extent that it becomes a trope. For their part, id Software took years to catch up with Valve - Doom 3 (2004) is extremely strongly influenced by Half-Life, but was released in the same year as Valve's phenomenal sequel. Half-Life 2 developed environmental design still further, achieving an even more seamless and immersive feel. Like Freeman himself between the events of Half-Life and Half-Life 2, Valve's series exists in a kind of suspended animation - but almost 20 years on, the original game remains a vital FPS experience, in no small part due to its environmental innovations.

2 Comments

Chris Lindsay

10/26/2017 11:08:43 am

Super article. Thanks!

Reply

PB

10/8/2021 04:20:03 pm

I think Goldeneye's environments were pretty coherent in 1997, being varied and believable locations instead of just random mazes like Doom maps. Although, they were distinct levels with no transitions.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|