|

Beginning in earnest in the 1960s, a British colony with a land area of less than 450 square miles spawned a commercial film industry of stunning vitality. At its peak, Hong Kong was the world's third biggest film producer, exceeded only by the United States and India. Its well-developed galaxy of movie stars made films of every genre which commanded huge audiences at home, across East Asia, and eventually the West. While film production has slowed dramatically since the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s, Hong Kong cinema is still an international cult phenomenon, its influence felt all over the world. This legacy rests on one thing above all - action movies.

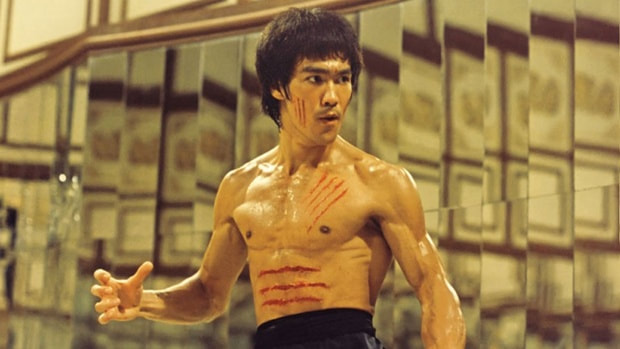

Despite the transformation of stars like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Michelle Yeoh into household names, and the contributions of directors like John Woo to American film, relatively few people in the West are watching Hong Kong action movies today. This is due in part to their fairly poor availability on home video and streaming services, a situation which is only slowly changing for the better. Quite often, seeing even the most iconic films is a matter of sourcing out-of-print DVDs, or even importing region-free discs directly from Hong Kong. What follows is my brief, personal introduction to the remarkable world of Hong Kong action cinema. With many hundreds of films made in the genre across the decades, a comprehensive guide is all but impossible - but the key films and further readings listed here should provide a point of entry into the most unique and thrilling action movies there are. Are you sitting comfortably? Then we'll begin. I: Hong Kong action: what's so special?

As a product of its unique cultural context and history, Hong Kong action film has a number of distinctive elements. These aren't consistently present in all movies and the list is not exhaustive, but they are a good starting point. The building blocks of the influential Hong Kong action formula include:

a) Frequent, intense and highly stylised action. Typically, action scenes in Hong Kong movies are more numerous, lengthy and carefully choreographed than their American counterparts. Action and fight choreographers have a prized position on many productions, and the corresponding Hong Kong Film Award is prestigious. A large proportion of actors have fight training and experience. Characters often execute feats of agility and endurance that would be seen as implausible in a Western film. b) A dynamic and sometimes jarring mix of tones. In general, Hong Kong films tend to be much less consistent in tone than Western ones - this is as true for action movies as for other genres. For example, deadly seriousness and comedy that borders on slapstick can be combined, sometimes within the same scene. It's fair to say this can take some getting used to but action-comedy has produced some of Hong Kong's most acclaimed and lucrative films. c) A greater role for women. While male-dominated narratives and outright misogyny certainly abound in Hong Kong film generally, women have long had a major on-screen role in the region's action cinema. Two notable eras of prominence for women in action movies include the wuxia ("martial hero") boom of the 1960s and the "girls with guns" trend in the 1990s. King Hu's 1966 film Come Drink With Me stars Cheng Pei-pei, and is a classic of the genre. Michelle Yeoh was born in Malaysia but came to prominence in Hong Kong and is arguably the greatest ever female star in action cinema. II: A (very) brief history of Hong Kong action cinema

Hong Kong's distinctive film culture, and specifically its action cinema, are a product of its unique history. Films have been made in Hong Kong for over a hundred years, with the first full-length production released in 1913. However, mainland China and specifically Shanghai dominated Chinese cinema for the whole of the first half of the 20th century. It was only after the emergence of the People's Republic of China in 1949 that Hong Kong came into its own.

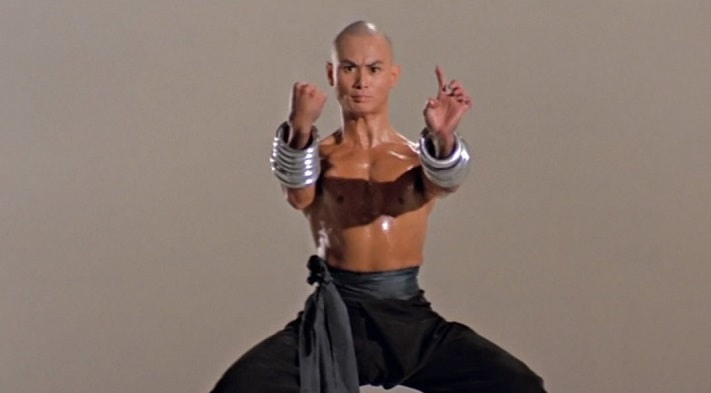

From the late 1950s, two studios struggled for control of the local film market - upstart Malaysia-based Cathay and the seasoned Shaw Brothers. The latter studio eventually achieved supremacy after 1964, when the death of Cathay's founder in a plane crash prompted a failed corporate reorganisation. Armed with its own massive studio lot in Clearwater Bay and a near-stranglehold on Hong Kong, Shaw Brothers proceeded to churn out many hundreds of films between the mid-1960s and early 1980s. While Shaw Brothers invested in many genres, martial arts movies were its mainstay. Wuxia stories and martial arts are a key plank of Chinese culture generally, and in film had long been a crowd-pleasing favourite across Asia. In one notable example, actor Kwan Tak-hing played iconic folk hero Wong Fei-hung in over 75 movies, including 25 in 1956 alone. From the 1960s, Shaw established a successful but highly rigid formula for its martial arts movies. Typically setbound with no location shooting, they are often based on wuxia novels and set in the distant past. A huge range of stars including David Chiang, Cheng Pei-pei, Ti Lung, and Gordon Liu were regular players. Key directors included Lau Kar-leung, King Hu, and the immensely prolific Chang Cheh. Ultimately, Shaw Brothers sowed the seeds of its own destruction. Their disgruntled head of production, Raymond Wong, broke away and founded rival studio Golden Harvest in 1970. It was Wong's dynamic new force which had the foresight to sign a deal with Bruce Lee and, after Lee's death, to make a star of Jackie Chan. The immense success of these stars could not be equalled by Shaw Brothers' increasingly archaic model and the venerable studio all but folded in the early 1980s. That decade saw the beginning of the "golden era" for Hong Kong action. Jackie Chan graduated to director and his action-comedy hit Police Story (1985) popularised stories set in present-day Hong Kong. Upstart "mini-major" studio Cinema City and producer-director Tsui Hark eventually rescued John Woo, then working in comedy, by enabling him to make his dream project. A Better Tomorrow (1986) fused the chivalrous bloodshed of Woo's mentor Chang Cheh with a contemporary crime tale and became a international smash. In the 1990s, film production in Hong Kong began to slow. The reasons included declining profits due to overproduction, the rise of piracy, anxiety over the upcoming handover in 1997, and the departure of key figures abroad - including action directors John Woo, Tsui Hark, and Ringo Lam. Numerous classics of the genre were made in the 1990s, but the writing was on the wall - today, two decades on from the handover the Hong Kong the industry is far smaller than at its peak. Increasingly, the centre of Chinese cinema in general and action movies specifically has returned to the mainland. III: Ten key movies to get started

A dozen Hong Kong film fans would provide a dozen different lists of classic movies to get started with. All of my choices were released between 1966 and 1991, but numerous great films were released in the 1990s and since 2000 - albeit at a slower rate than in the industry's glory days. Most of these ten are fairly easy to get hold of, with a few even being on Netflix.

Come Drink With Me (1966) - Directed by King Hu One of the essential Shaw Brothers classics, Come Drink With Me was directed by legendary perfectionist King Hu. Soon, the Taiwan-born director would leave the studio to pursue his grander artistic vision. "Queen of swords" Cheng Pei-pei stars as Golden Swallow, a young warrior on a secret mission. A sequel followed in 1968. The One-Armed Swordsman (1967) - Directed by Chang Cheh At his peak, Chang made several movies a year for Shaw Brothers. With The One-Armed Swordsman he set out his personal vision: bloody, highly masculine revenge stories with a strong emphasis on codes of brotherhood and honour. The film made a star of Jimmy Wang Yu and spawned numerous sequels and remakes. Enter the Dragon (1973) - Directed by Robert Clouse Sometimes inexplicably dismissed as an "American movie", Enter the Dragon is Bruce Lee's most complete statement as an action star and one of the most iconic and explosive films of the 1970s. Arriving at the peak of the martial arts boom in the United States, it popularised the reliable "tournament film" formula and immortalised Lee's persona. The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978) - Directed by Lau Kar-leung Formerly an action director for Chang Cheh, Lau began directing in 1975 and with his fourth effort made one of the most celebrated martial arts movies of all time. Gordon Liu stars as a young scholar who flees to the legendary Shaolin Temple and trains to overthrow the oppressive Manchu rulers. Arguably the ultimate martial arts training film. Drunken Master (1978) - Directed by Yuen Woo-ping A radical new take on the Wong Fei-hong character, played by emerging star Jackie Chan not as a wise sage but as a rebellious youth. Drunken Master helped popularise action-comedy, and master action director Yuen Woo-ping would go on to work on The Matrix and Kill Bill. The Prodigal Son (1981) - Directed by Sammo Hung Together with classmate Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao formed the core of the "Seven Little Fortunes" troupe who would transform Hong Kong action. Directed by Sammo and starring Yuen, The Prodigal Son is set within the Cantonese opera world which so influenced Hong Kong action cinema. Co-star Lam Ching-ying's fighting is stellar. Yes, Madam (1985) - Directed by Corey Yuen Yet another member of the Fortunes, Corey Yuen directed this action-comedy which is said to have initiated the "girls with guns" wave - although it's largely based on martial arts. Cynthia Rothrock became the first Westerner woman to star in a Hong Kong movie, partnered with a young Michelle Yeoh, soon to be Hong Kong's greatest female action star. Police Story (1985) - Directed by Jackie Chan Disillusioned with his faltering attempts to break America, Jackie returned to Hong Kong and made one of the most influential and successful action-comedies of all. Chan plays a cop who becomes the target of a mobster's deadly vendetta, and executes some of the most remarkable stunts ever caught on camera - not to mention some terrific fights. A Better Tomorrow (1986) - Directed by John Woo A loose remake of the 1967 film Story of a Discharged Prisoner, John Woo's A Better Tomorrow inaugurated a thrillingly new style of action. "Heroic bloodshed" emphasises kinetic gunplay, themes of brotherhood, and a bodycount in the hundreds. Woo would make six more films in the genre up until 1992, but this is a pivotal moment. Once Upon a Time in China (1991) - Directed by Tsui Hark By casting Jet Li as a yet another reimagined version of the iconic Wong Fei-hong character, Tsui Hark reinvigorated period martial arts cinema for the 1990s. Rosamund Kwan stars as "13th Aunt", while Yuen Biao appears as Wong's student Leung Foon. The film would spawn five sequels. IV: Hong Kong action movies and availability

There's no shortage of fantastic Hong Kong action movies. Unfortunately, they do have a very significant availability problem both on home video and streaming services. Today, there are few distributors seeking to release either older or new Hong Kong movies in the UK. This is in contrast with the peak of the DVD era in the early- to mid-2000s, when labels like Hong Kong Legends released many films. Seeking out second hand copies of these old discs remains a key way to see some of the classics of the genre. It's also possible to import DVDs and Blu-rays from Hong Kong via eBay and sites like Yes Asia but this can be very costly.

There are some bright spots in this picture. Celestial Pictures control the rights to the Shaw Brothers library, and have made dozens of martial arts films available on Amazon Prime and Google Play. Recently, these have also gradually begun to appear on Netflix. Eureka Video have recently begun to release lavish Blu-ray reissues of Hong Kong action films, so far including Iron Monkey, the first three Once Upon a Time in China films, Police Story and Police Story 2. Recent mainland Chinese action films are sometimes easier to come by, and often feature the involvement of Hong Kong figures like director Dante Lam. The reasons for the relatively poor availability of Hong Kong movies in the West, despite the advent of streaming services, are probably varied. Unfortunately, interest in Hong Kong cinema has probably declined since the mid-2000s, while interest in South Korean cinema for example has risen (South Korea is sometimes called "the new Hong Kong"). Some films also use music taken under dubious circumstances from other sources, including some key films by John Woo, which may be an impediment to their re-release. Still, the recent bright spots such as Celestial's promotion of the Shaw Brothers library and a trickle of films making it into Netflix may point at a brighter future for the availability of Hong Kong movies. The resurrection of the Hong Kong film industry as a major force seems most unlikely, but hopefully more of the classics of the glory days will be accessible to all.

What was your introduction to Hong Kong action cinema? How would your list of top ten movies for newcomers differ from mine? Hit that comment button...

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|