|

In 2003, the New York Times published an article casting judgement on which show was “the best spy series in television history.” The writer, Terence Rafferty, wasn’t thinking of the then-current hit series 24. He was writing about an obscure British series which had barely been broadcast in the United States - The Sandbaggers.

To this day, Rafferty’s words obviously provide a perfect quote for the back of DVD box sets. Despite his effusive praise and a small cult following, though, The Sandbaggers remains barely known in the country where it was made. More than 40 years since its final episode was first broadcast, the series remains one of the best of its kind. Spy fiction is a permanent fixture in British culture - and The Sandbaggers deserves to be seen as one of the jewels in the crown.

If the glamorous James Bond mythos created by Ian Fleming is the first great tradition in British spy fiction, then The Sandbaggers is a classic of the second - the more cynical, murky, and realistic approach favoured by writers like John le Carré and Len Deighton. The show was created by the writer Ian Mackintosh, and three series were made for ITV - one shown in 1978, and two in 1980.

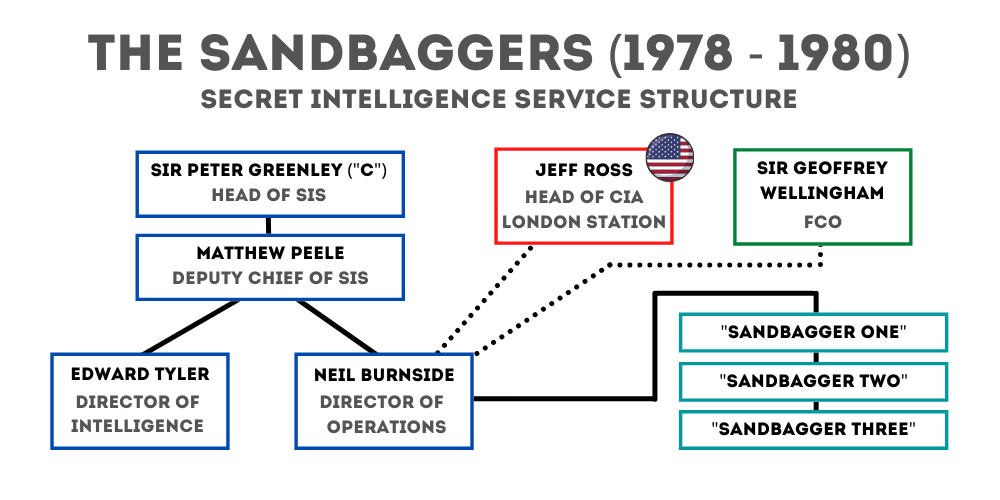

The show is set in the then-present day, a time of Cold War tension. Around the world, Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service - popularly known as MI6 - pursues a covert conflict with the Soviet Union. In this effort, it often acts as a junior partner to the United States in the unequal “special relationship”. The “Sandbaggers” of the title are the three field agents of the SIS Special Operations Section, the nearest thing to 007 in this realistic take on the struggle for Cold War supremacy. The world that the Sandbaggers inhabit is a far cry from the glamour enjoyed by James Bond. The agents are underpaid, understaffed and under equipped. Much of their day is consumed by paperwork inside the grey concrete edifice of their London headquarters. This humdrum existence is occasionally punctuated by a field mission, during which they may be made to risk their lives at the behest of “some idiot in Whitehall”. This description of a Sandbagger’s life is spoken by their immediate superior, Neil Burnside. Played wonderfully by Roy Marsden, Burnside is the SIS Director of Operations (or “D-Ops”) and himself a former Sandbagger. Responsible for overseeing field missions, Burnside is vastly unlike the typical central character of most TV series. A cynical, ruthless, and insubordinate schemer, he is difficult to like. He believes that the Service’s mission should be the “total destruction of the KGB”, and is at one point described as being so right-wing that he “makes Attila the Hun look like a member of the Tribune Group.” As repellent as Burnside can often be, he also has brilliance in abundance and typically outwits his opponents in the end. He is also - usually - fiercely protective of the Sandbaggers, whom he sees as undervalued by the SIS hierarchy. The agents themselves have a smaller role in the series, but the dependable Willie Caine is another key character. Played by Ray Lonnen, he is a former soldier from a working-class background with an intense dislike of violence - which is sorely tested on occasion by the nature of his work.

While it has its occasional moments of action, The Sandbaggers is much more low-key than today’s spy shows. While the low budget and 70s production values go some way to explaining this, the subdued style is also a consequence of Ian Mackintosh’s specific view of espionage. In his world, Burnside and the Sandbaggers are involved in internal battles within the Service as much as they are in missions overseas. For D-Ops, the very survival of his unit depends on skillfully navigating office politics that in their own way can be as cut-throat as a KGB assassin.

Almost every episode contains verbal duels between Burnside and one or more of a triangle of superiors. Within SIS, he answers to the fatherly “C”, Sir James Greenley. The character is played by Richard Vernon, who had a small role in Goldfinger in 1964. While Burnside’s relationship with C is cordial, he has more combative exchanges with his deputy Matthew Peele, played by Jerome Willis. An even more complex relationship exists between Burnside and his former father-in-law Sir Geoffrey Wellingham, a powerful civil servant overseeing SIS who is played by Alan MacNaughton. Wellingham is at the centre of some of Burnside’s most dubious schemes, which often best demonstrate the supremely cynical, bleak view of the world reflected in The Sandbaggers. In one memorable instance, Burnside stoops so low as to exploit his ex-wife’s unhappiness for political advantage - he implies that he would rekindle the relationship in exchange for a favour from Wellingham. In another instance, Burnside resolves to do anything to prevent C being replaced by a new appointee who shares a mutual hatred with D-Ops - even if it means putting someone Burnside believes is an incompetent into the post instead. Even when the main point of conflict is outside the SIS building, in the world of The Sandbaggers an ally can be almost as dangerous as an enemy. Not infrequently, Burnside and his agents find themselves stonewalled, lied to, and even directly betrayed by supposed allies like France, West Germany, and the United States. The theme of ruthless jostling for competitive advantage, in which human lives are freely traded for political and commercial gain, is a fascinating but unsettling aspect of the series. It is easy to believe that this portrayal, which has won plaudits from some right-wing commentators, is closer to the truth than most spy fiction. Even so, The Sandbaggers reflects a much gloomier portrait of Britain’s place in the world than almost any other spy show. There is little sense that SIS is capable of actually deflecting the operations of the KGB, and the CIA is obviously by far the superior partner in their alliance. Indeed, the UK is so inferior to the Americans and so dependent upon their support, that on more than one occasion SIS has to conceal its own knowledge of CIA betrayals to avoid damaging the “special relationship”. The impression created is that the UK is a faltering country on the decline, falling back on every dirty trick in the book in a bid to shore up its fading power in the world. Given what we know about the country’s real-life shabby “post-colonial” activities in Oman, Sri Lanka, Kenya and elsewhere, this is a convincing portrayal. To enter into too much detail about events in The Sandbaggers would be to risk ruining the intricacies of its 20 episodes. Rest assured, however, that its crackling dialogue and ingenious plotting more than make up for the primitive production values. Neil Burnside in particular should, by rights, be considered one of the all-time great characters in spy fiction - a cold, angst-ridden operator who is far away from 007 as a spy could be, and yet just as compelling in his own way. In the third series of The Sandbaggers, a few episodes were of a noticeably lower quality - particularly the preachy “My Name is Anna Wiseman” and the pedestrian “Sometimes We Play Dirty Too”. These were written by outside writers, and not by series creator Ian Mackintosh. The reason was because before he had finished writing the series, Mackintosh was in a plane which mysteriously disappeared off the coast of Alaska in July 1979. It was an incident that is as murky and intriguing as any episode of the superb spy series that the writer had created.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|