|

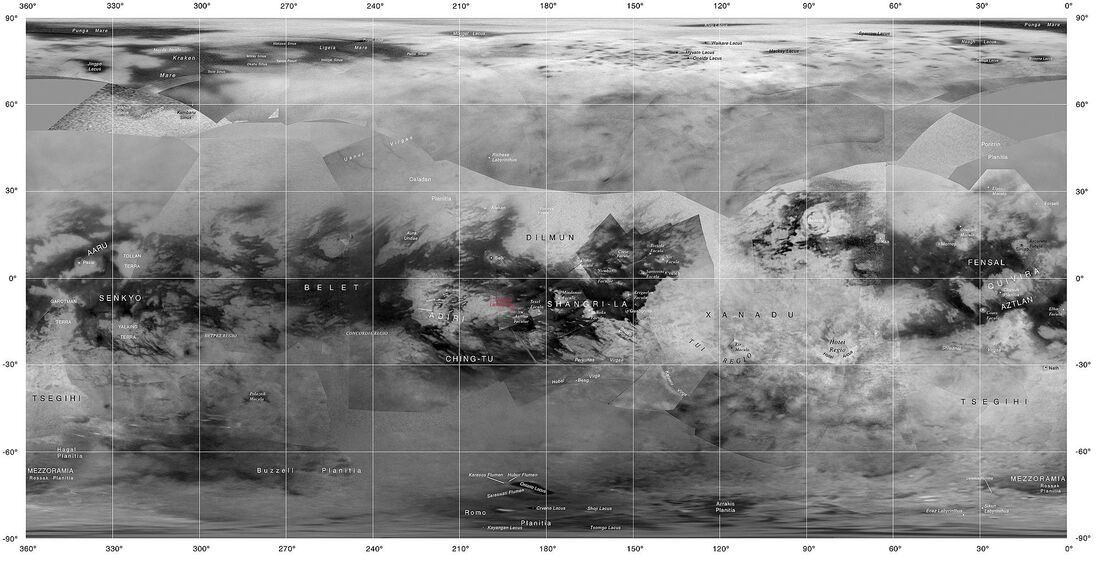

It is 2276 and the Earth is a utopia. The population is only half a billion, crime and conflict are things of the past, and what we now call rewilding has taken place on a planetary scale. To Duncan Makenzie, this world is a deeply strange and confusing place. He is a scientist-administrator from humankind’s outermost colony - Titan, the largest of Saturn’s moons. Accepting an invitation to celebrate the quincentennial of the United States, Duncan visits Earth for the first time and must also handle sensitive business of his own.

Imperial Earth is the second of three novels Arthur C. Clarke published in the 1970s. Two of those novels are widely acclaimed classics, well-known today. Rendezvous with Rama (1973) is famed for its sense of wonder and won five major awards. The Fountains of Paradise (1979), popularised the concept of the space elevator and won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novel. Despite Clarke’s high hopes for it - at one point he thought of it as “the big one” - Imperial Earth did not reach these heights. It won no awards and eventually fell out of print, where it remained for some time. The novel has returned to print, and today Imperial Earth joins Clarke’s other 1970s novels in Gollancz’s authoritative SF Masterworks collection. In his introduction to this edition, SF author Stephen Baxter mentions some of the book’s interesting themes. These include its greater emphasis on human relationships, its focus on economics, and Clarke’s position as a “technophilic optimist”.

Imperial Earth is not a particularly plot-oriented novel. In 2010, Jo Walton summarised its plot as “what I did on my summer holiday”, which is not entirely unfair.

By 2276, humans have solved most of the longstanding problems on Earth and have spread across much of the solar system. The frontier is represented by Titan, the inhospitable moon of Saturn which is the most distant world occupied by humans. Titan is critical to the system’s entire economy because it is a prolific source of accessible hydrogen needed to power spacecraft. It is also the dynastic fiefdom of the Makenzie family, who founded the colony and control the hydrogen supply. Duncan Makenzie is a third-generation clone. He is a clone of his “father” Colin, who himself is a clone of Duncan's “grandfather” Malcolm. The three of them and their respective families largely run Titan but are conscious of the economic threat represented by the new “asymptotic drive” which consumes far less hydrogen. When the family receives an invitation to Earth to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the founding of the United States, Duncan is selected to attend. Duncan travels to Earth aboard the spacecraft Sirius, along with over 300 other passengers. While the Makenzie clan intend to sincerely celebrate the quincentennial, Duncan has additional motives for the trip. He plans to seek out former lovers, Calindy and Karl, and to organise the creation of his own clone as a means to secure his family’s future. While on Earth, Duncan must acclimatise himself to a world he has never visited and which seems deeply alien to him. He also finds himself trying to understand the motives of Karl, which might provide the seed of a different economic future for his own world.

The future presented in Imperial Earth is very much in keeping with Clarke’s usual style. The setting is free of conflict, and broadly unencumbered by serious problems. War and crime are things of the past, the Earth’s environment has been revitalised and safeguarded, and humans have colonised much of the solar system. In terms of setting, then, the novel shows how little Clarke’s style evolved over the years. With just a few changes, Imperial Earth could be made into a sequel of sorts to Earthlight (1955); it could just as easily be set alongside a much later book like The Hammer of God (1993).

In all of these books, Clarke presents peaceful and prosperous futures made possible by great strides in technology and understanding. Part of the pleasure of reading them is that in each one, Clarke speculates about different aspects of near-utopian future worlds. In Imperial Earth, this includes discussions of a worldwide communications network that resembles the Internet, the reintroduction of forests and threatened species, and a human population that is spread more thinly and harmoniously across the system. Imperial Earth is also notable for its emphasis on human relationships. Like many other SF authors of his generation, Clarke was not particularly adapt with characterisation. In his books and stories, people are engines of plot and spokespersons for ideas, rather than fully-formed personalities. By contrast, Duncan Makenzie does have something more of an inner life. His relationships are also a significant part of the book. For example, he has a strong link with the estranged former wife of his clone “grandfather”, who works on geological problems in seclusion on Titan. There is also an element of sexuality to Imperial Earth. Prior to the novel’s events, Makenzie was in a kind of polyamorous relationship with both a man and a woman. In this sense, the book is somewhat groundbreaking, and fits within the context of greater sexuality in science fiction in the 1970s. However, Clarke is very coy about these subjects, just as he was in discussions of his real personal life. Much more is implied than ever actually stated. Truly frank discussions about sexuality in SF would be left to bolder authors like Samuel R. Delany.

Imperial Earth is an interesting SF novel which fits neatly within Clarke’s wider body of work. It is not one of the author’s most important books, however, and certainly pales in comparison to its immediate predecessor, Rendezvous with Rama. A number of its themes - such as cloning and environmentalism - have been explored more thoroughly elsewhere. What Clarke does do in the book is to combine these themes into another of his cohesive and concise explorations of a better world.

The strongest part of the novel is arguably its finale. In keeping with Clarke’s style, it is based not on heroic action or a momentous event, but rather on an inspiring speech. In his capacity as a representative of Titan, Makenzie speaks eloquently to an audience of millions about humanity’s place in the universe. Clearly, the protagonist is being used as a mouthpiece for Clarke’s own views - but this knowledge does not diminish the power and hope of those words. In a way, then, the speech is a microcosm for Clarke’s work.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|