|

Five books into her Hainish cycle, it is clear that one of Ursula K. Le Guin's goals with the series is to explore different ways of being, different kinds of society and how they interact. In doing so, Le Guin achieves what the best science fiction writers do - making readers consider other ways of life, and how they may compare with and improve upon their own. In her 1974 novel The Dispossessed, the sixth in the cycle, Le Guin does this more powerfully than ever before.

In this book, a number of distinct societies are compared. Its main character personally explores the two main societies, with others present in the background. He compares these systems within the narrative, judging one that is familiar to him against one to which he is new. While his society is in some senses a utopia - famously described as an “ambiguous utopia” - he is compelled to imagine a way of life that is better still, and so are we.

While The Dispossessed was the sixth Hainish book to be published, it is set earlier in time than any of the others. The mathematical theory that will eventually lead to the development of the ansible - an instantaneous communications device prominent in other books - is a subplot of this novel. The date of the novel’s setting has been suggested as something like 2300 AD. At this point in the series’ history the people of Hain have not yet set up the Ekumen, their interstellar federation of worlds, in part because this enterprise will require the ansible.

One of the worlds already contacted by Hain by this time is Urras. A large, Earthlike planet, it is the main habitable world in the Tau Ceti system. Urras is a very clear analogue for the world of the 1970s in which Le Guin was writing. Like the Earth of that time, Urras is divided into states and two superpowers control much of its surface. A-Io is a capitalist regime clearly modelled on the United States, and Thu is a communist state little discussed by the novel but obviously an analogue for the Soviet Union. Le Guin had done something similar with her earlier novel The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). However, there is another crucial location in the novel - and one from which the book takes its title. Long before the story begins, a group of dissidents from Urras were allowed to leave the planet and set up a new society on the nearby moon, Anarres. Formerly merely a mining colony, Anarres becomes a sparsely-populated world of its own where society is organised along anarchist lines. There is no government per se, no law, and life is based on the principle of mutual aid. The systems of the two worlds interact with their distinct local ecological profile - Urras is a verdant and Earthlike world being ravaged by the waste and exploitation inherent in capitalism, and Anarres is a harsh desert environment where life is made possible only by intense cooperation. The novel strongly implies that capitalism will cause ecological catastrophe on Urras. This fate has already befallen Terra - formerly known as Earth - which has become a wasteland. This sets up the earlier Hainish novel The Word for World is Forest (1972) and forms part of Le Guin’s critique of capitalism and her somewhat prescient emphasis on environmentalism. The novel’s central character is Shevek, a gifted physicist and a native of the anarchist world of Anarres. Like the 20 million other residents of his arid world, Shevek is a participant in a society radically different to our own. On Anarres, solidarity is the guiding principle of social organisation. There is no money, no market, and no private ownership. People accept job postings only if they choose to, switching between their personal specialism and the less obviously rewarding physical labour upon which civilisation depends and in which most people share. This strikingly different way of being is reflected in the way the people of Anarres speak - in their language, no one would refer to “my mother”, but merely “the mother”. While people are in many ways radically free there, life on Anarres is far from perfect. The planet’s challenging ecological conditions mean that whole populations endure periodic hunger, and life is necessarily simple. Shevek also finds that a kind of hierarchy is creeping into Anarres, despite the pervasive teachings of “Odonianism”, the solidaristic system of thought that underpins society. His academic colleagues refuse to take Shevek’s remarkable work in theoretical physics seriously, and this catalyses his momentous decision to travel to Urras - the first person from his world to do so since the founding of the anarchist society.

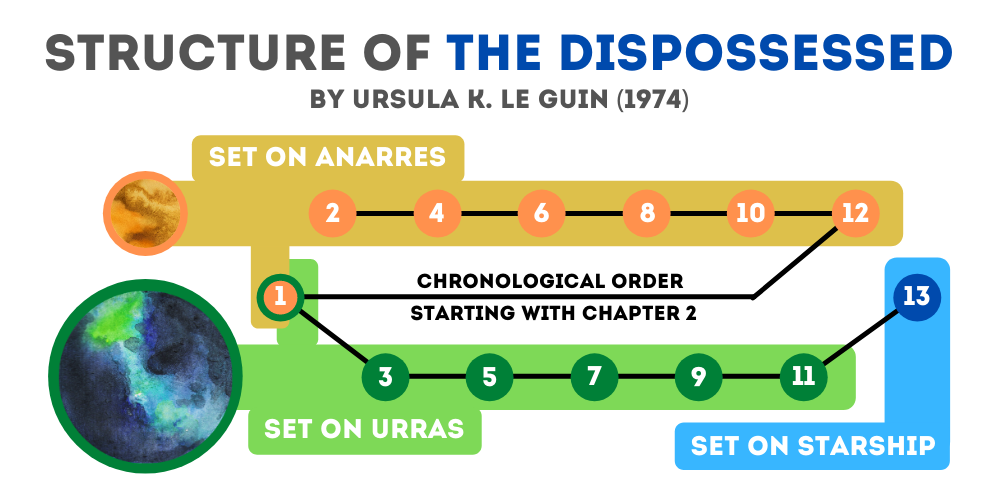

One of the strengths of The Dispossessed is its unusual structure. The novel has thirteen chapters. The first and last chapters are set in transit between planets, and the remaining eleven are split into two threads. One thread of six even-numbered chapters is set on Anarres and occurs first chronologically, while the other thread of five odd-numbered chapters is set during Shevek’s time on Urras and occurs last chronologically. This means that the novel starts not at the beginning, but in the middle of its narrative and builds towards not one but two “climaxes”.

This structure, which reflects Le Guin’s growing experimentalism in the 1970s, can be confusing at first but serves to aid the author in her comparison of two radically different societies. While on Anarres, Shevek relates how undesirable labour is shared between many members of the community. In a subsequent chapter, he learns that on Urras, an impoverished and exploited underclass are forced by capitalism to undertake these tasks. With The Dispossessed, Le Guin is clearly deeply motivated by a desire to provoke readers to recognise not only how exploitative and corrosive capitalism is, but also to realise that alternatives do exist, and are possible. Crucially, the advantages to life on Anarres are achieved without the aid of advanced technology. In most respects, life there is less technology-centric than in our real world. This reflects Le Guin’s relatively minor interest in technology compared with most other SF writers, and also reinforces the plausibility of alternative ways of being. The novel reminds us that space travel, artificial intelligence, and robotics - the staples of much SF - are not prerequisites for a better life or a fairer society. What holds humankind back, Le Guin argues, is not human technology but rather human will and imagination. Shevek finds himself to be no more free to publish his work on Urras than he was on Anarres and witnesses first-hand a brutal reprisal when the people of the capitalist world attempt to rise up. As the story draws to a close, he finds an ally in the Terran diplomatic representative to Urras, and his final actions help sow the seeds of the Ekumen, the League of Worlds, which is a critical element of the other Hainish novels, published earlier but set later in Le Guin’s fictional timeline. This enables Shevek to finally find a way to share his brilliance with the whole of the human family, unconstrained by either bureaucracy or profit. Like The Left Hand of Darkness before it, The Dispossessed is a world away from the traditional idea of science fiction. Relatively unconcerned with technology, Le Guin instead explores a wide variety of political, philosophical, and economic ideas with a profoundly humane and thoughtful approach. The book is not dense in plot terms, but its engagement with ideas is impossible even to summarise here. While reading the novel benefits from an awareness of the other Hainish books, it stands up impressively in isolation and its acclaim is richly deserved.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|