|

Recent years have seen the rise of feminist dystopias - stories focusing on societies in which women are an oppressed underclass. Building on and examining the actual sexism in our real, contemporary world, these works represent a significant trend in social science fiction. It has been suggested that the uptick in this genre has coincided with specific real-world developments, especially in the United States - notably the Trump presidency and the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

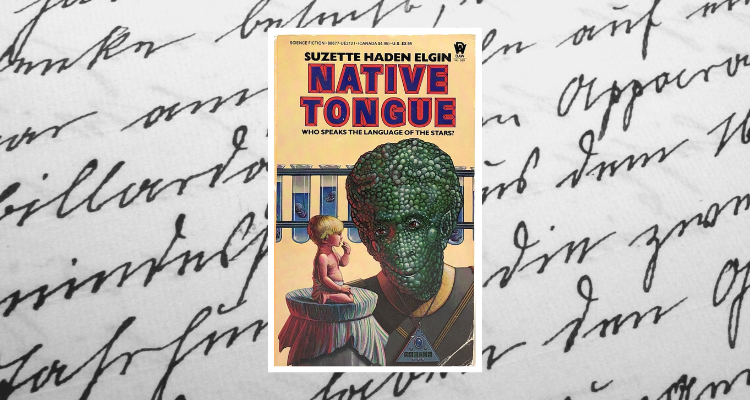

Probably the best-known feminist dystopia, however, is much older - Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale. The book was a major success at the time, and was popularised again by the TV adaptation which premiered in 2017. But The Handmaid’s Tale was not the first book of its kind. Published in 1984, Native Tongue is a science fiction novel by Suzette Haden Elgin which also takes the form of a feminist dystopia. It uses a different approach to Atwood’s work, partly because it fuses its feminist message with discussion of a particular science, and Elgin’s profession: linguistics.

Native Tongue is set in a dark vision of the United States, primarily in the late 22nd century. Women possess virtually no rights at all, and society is a rigidly enforced patriarchy. Humans have, however, become a notable spacefaring power and have set up numerous colonies on other planets. Linguistics has risen to become absolutely critical in this world, because humanity’s access to key materials depends on the ability to communicate with alien species. For this reason, a small group of dynastic linguist families known as the Lines have acquired immense power.

Language, then, becomes a fundamental pillar propping up an oppressive society - but it may also be the tool which could free women from their near-enslavement. Native Tongue revolves around three plot threads, which begin distinctly but gradually intersect:

While Elgin’s interweaving of these threads is quite deft, Native Tongue is not what could be called an eventful novel. The majority of the book is carried by dialogue, and the author makes few efforts to really describe her dystopia in any depth. This contributes to a key weakness of the book, which is that the dark future scenario doesn’t feel very plausible. Elgin’s future history posits that the nineteenth amendment of the United States constitution was repealed in 1991; only seven years after the book’s publication. Also, the Lines are said to be reviled by the rest of the population, who view them as greedy and living in luxury. Conversely, the families of the Lines have an ascetic existence, so this animosity makes little sense. The way in which Elgin fuses her themes also undermines her feminist message. In this vision of the future, humans have become a major interstellar power despite eliminating women from almost all areas of public life. One of the author’s hopes for Native Tongue was that it would help to popularise the quite functional constructed language she devised for it. In the story, women consigned to “barren houses” create a unique women’s language called Láadan. The language had been invented by Elgin in 1982, partly as a test for the famous Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Its aim was to serve as a means to communicate in a specifically women-centric way. Láadan did not catch on, and Elgin lamented it as a failure, especially compared with Klingon, which she described as “as masculine as you could possibly get”. Arguably, Elgin was much too hard on herself in this respect. It could be argued that Klingon caught on not because it has any special utility, but merely because it is associated with Star Trek, a vastly popular, multi-billion dollar franchise. Láadan, by comparison, largely exists only in a relatively obscure science fiction novel. It barely had any chance to find a following; nevertheless, Elgin concluded that women saw no need for a new, constructed language. Native Tongue is really much more successful as a thought experiment than as a novel. Somewhat frustratingly in story terms, it does not so much end as simply stop; almost all of its plot threads are left unresolved. While the book has two sequels, the thin characters are unlikely to inspire readers to pick them up. What Elgin did do, however, is to thoughtfully explore both a unique take on a feminist dystopia, and the science of linguistics. It is just unfortunate that those two could not be combined more smoothly, or within a more satisfying narrative.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|