|

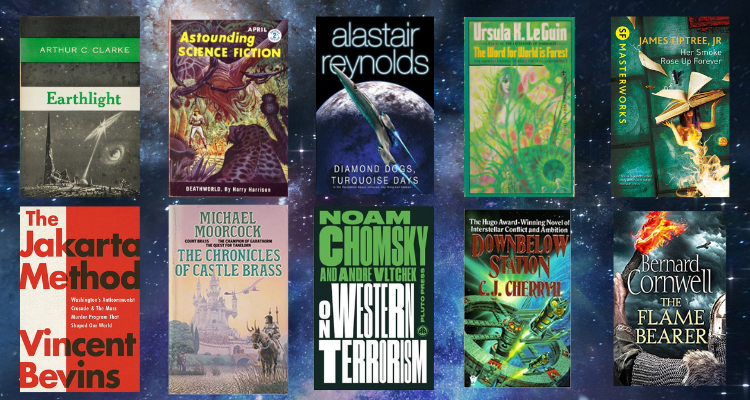

After falling agonisingly short in 2019, this year I'm on track to finish 50 books. Of these, I've listed the ten that I enjoyed most and that I'd definitely recommend. As was the case last year, I've read a lot of classic sci-fi, but below you'll also find a chilling non-fiction book from this year, fantasy by Michael Moorcock, and historical fiction by the peerless Bernard Cornwell. Earthlight (1955) by Arthur C. Clarke (Read more) This year I read Childhood’s End (1953), considered by many to be Arthur C. Clarke’s best novel. However, I much preferred his later book Earthlight. Based within a very well-imagined and convincing setting on the Moon, this brisk and engaging book focuses on a lowly accountant being compelled into acting as a spy for Earth’s government. Tensions are rising between Earthbound societies and the people who live on the outer planets, and the Moon looks set to be a major flashpoint in a coming conflict. As ever with Clarke’s work, the characters are thin but his setting is very engaging. In addition to depicting life on the lunar landscape in a convincing way, the book also cleverly incorporates influences from the Cold War which was ongoing at the time it was written. Clarke’s books are hardly known high-action, but there’s a single, solitary but gripping space battle at the climax. Earthlight isn’t one of Clarke’s most famous books, but one I would definitely recommend. Deathworld (1960) by Harry Harrison (Read more) Harry Harrison was an author known for his wit and flair for satire, and for his ability to incorporate challenging ideas into exciting stories. Deathworld, his first novel, has all of these strengths. The story concerns a gambler who is forced to visit Pyrrus, a planet with an entire ecosystem which is extraordinarily hostile to humans. The human colonists have adapted by becoming extremely strong, well-trained, and heavily armed but their numbers are still dwindling year on year. While the protagonist Jason dinAlt becomes involved in a lot of bloody battles for survival with the vicious local flora and fauna, the story is just as much a vehicle for messages about environmentalism, the need to embrace change, and the importance of understanding and communication. Harrison wrote sequels which were published in 1964 and 1968, but the original is arguably the best and certainly the most influential. A number of later sci-fi works featuring “deathworlds” of their own have a debt to Harrison’s first classic. Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days (2003) by Alastair Reynolds (Read more) Two superb novellas are collected in the collection, Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days. Both are set in Alastair Reynolds’ sprawling Revelation Space universe, but don’t require any prior knowledge of the other books. Taking place in a frequently hostile and terrifying universe, both stories focus on people grappling with transformative experiences at the bleeding edge of human endurance. In “Diamond Dogs”, a group of explorers try to defeat a cruel, mysterious maze apparently constructed by ancient aliens - a quest which increasingly demands that they sacrifice their humanity to succeed. In “Turquoise Days”, dark truths are uncovered on a planet dominated by a super-ocean inhabited by organisms called “pattern jugglers” which have the ability to rewire the human brain. With these stories Reynolds displays a fantastic flair for mind-bending ideas and stomach-churning violence, but tempers these elements with a sly wit. The Word for World is Forest (1972) by Ursula K. LeGuin (Read more) After Ursula K. LeGuin died in early 2018, I made a commitment to seriously get into her work. Having now read 11 of her novels, The Word for World is Forest is probably my favourite so far. Less subtle than much of her work, the book was published during the Vietnam War and represents a scathing attack on that conflict. Set on a distant planet which humans are ruthlessly exploiting for its natural resources, the book switches between three viewpoint characters. LeGuin rarely wrote about true villains, but the humans in The Word for World is Forest are mostly truly appalling, and LeGuin’s sympathies are fully with the downtrodden local alien population. Even today, the book’s strident positions against militarism, racism, and environmental exploitation are deeply relevant. Her Smoke Rose Up Forever (1990) by James Tiptree Jr. During the 1970s, the sci-fi writer James Tiptree Jr. rose to prominence in an unusual way - purely on the strength of his short stories, not writing any novels until much later. Tiptree won the admiration of contemporaries like Harlan Ellison, Robert Silverberg, and Ursula K. LeGuin but what they did not know was that Tiptree was actually a woman named Alice Sheldon. Using her male pseudonym, Sheldon was able to infiltrate into the sci-fi market a number of superb and subversive stories, eighteen of which are collected in Her Smoke Rose Up Forever. The stories are dark and disturbing - the very first one deals with an apocalyptic pandemic, and the second with an outbreak of men murdering women on a mass scale - but in their own way uplifting and inspiring. Sheldon’s feminism and concern for the environment still stand out today. The Jakarta Method (2020) by Vincent Bevins While I read very little non-fiction in 2020, I’m very glad that I took the time to read The Jakarta Method by Vincent Bevins. I became aware of this disturbing but hugely important book due to Bevins’ blitz of podcast appearances early in the year, but these could not do justice to the breadth of his work. The Jakarta Method focuses on the appalling but little-known genocide which took place in Indonesia in 1965, and which targeted leftists. Devastatingly effective in terms of destroying mass movements in the country, the killings were supported by the United States and became, Bevins argues, a model for similar killing programmes elsewhere. Drawing together the human stories of the massacres but also retaining a global, historic focus, the book is an extremely useful insight into the murderous logic of US-backed anticommunism which exists in another form today. The Chronicles of Castle Brass (1973 to 1975) by Michael Moorcock Michael Moorcock’s fantasy novels are so compelling, fast-paced, and concise that I’ve managed to read 12 of them in 2020 alone, more than one-fifth of the books I’ve read all year. My start with Moorcock was the History of the Runestaff series, four brilliantly pulpy books that form a part of the author’s sprawling Eternal Champion cycle. More recently, I read The Chronicles of Castle Brass, a trilogy which serves as a conclusion to the Runestaff series, and at the same time to the whole Eternal Champion mythology. Moorcock cleverly combines different aspects of his various series together, including bringing in his more famous character Elric of Melniboné. All of this is far more inventive what Disney would call the “most ambitious crossover of all time”, decades later. Moorcock is living proof that when it comes to storytelling, real and subversive imagination beats corporate groupthink every time. On Western Terrorism (2013) by Noam Chomsky and Andre Vltchek The late Andre Vltchek, who died in September 2020, and Noam Chomsky collaborated in an unusual way on this wide-ranging book. On Western Terrorism wasn’t written as a book per se, but is essentially the transcript of a two-day conversation that the authors had at Chomsky’s workplace, MIT. In it, the pair discuss the history of interference by wealthy Western countries into the affairs of poorer states, and in particular to prevent those states from exploiting their own resources as they see fit. The book ranges across a huge span of time and across dozens of countries, and draws on the authors’ enormous wealth of knowledge and experience. While it doesn’t go into tremendous detail on any particular cases, On Western Terrorism is easy to recommend as a brisk introductory tour of the ways in which wealthy nations impose their will on poorer ones, despite their hollow claims to believe in liberal democracy. While Chomsky is the big name out of the two authors, Vltchek certainly holds his own and his loss is a very real one. Downbelow Station (1981) by C.J. Cherryh (Read more) 2020 has been my first year reading C.J. Cherryh, and as yet only one of her books has made an impression - but that novel, Downbelow Station, has a lot to recommend it. One of the definitive space station stories, the book takes place on a facility which represents a key link in a chain linking Earth with distant stars. Cherryh crafts a universe with numerous conflicting factions and a huge cast of characters, but manages to keep it comprehensible. Some may find the pace of Downbelow Station to be a bit slow, and the book is very dense, but it gradually builds up to a very satisfying conclusion. It’s early days, but it seems to me so far that Cherryh does better with a big canvas like this than with her shorter novels, where her languid pace prevents very much from happening within the scope of one book. The Last Kingdom books 7-10 (2013 to 2016) by Bernard Cornwell

Some things are predictable and reliable: the sun will rise, the world will turn, and Bernard Cornwell will deliver a satisfying novel every year. We have American labour laws to thank for a part of this, as Cornwell was denied a work permit when he moved to the states, wrote a novel instead, and has subsequently amassed a huge bibliography since 1981. This year I read the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth novels in his The Last Kingdom series, which focuses on the period when Vikings were invading what would become England. While the series could be accused of being a little repetitive at times, the quality just doesn’t dip and Cornwell delivers a rollicking story every time. As of 2020 the series is now finished at 13 books, but happily the Netflix series which began adapting them in 2015 has proven a success and hopefully will run for some years to come.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|