|

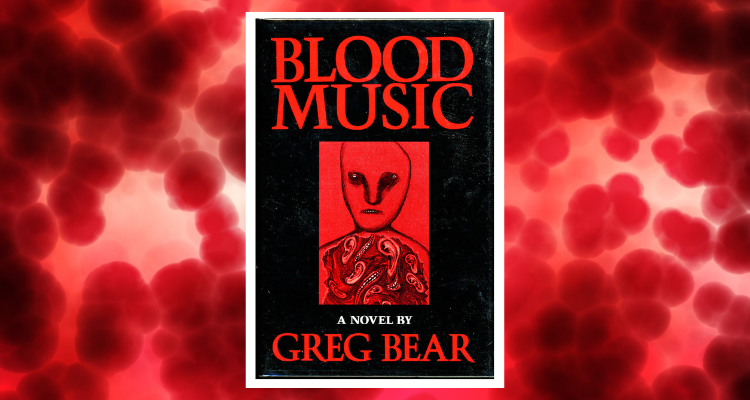

American science fiction author Greg Bear, who passed away in 2022, had a major success with his 1985 novel Blood Music. An expansion of his award-winning 1983 short story, the novel is themed around emerging sciences of the 1980s: biotechnology and genetic engineering. Both unsettling and in a way inspiring, the book confronts the massive implications of a new kind of artificial, biological intelligence run amok.

In the story, a renegade scientist based in a realistic, contemporary California uses his own lymphocytes to create what he calls “noocytes”, or thinking cells. What begins as an experiment in information processing brings seismic changes first to the scientist’s body, then to the people around him, and later to the whole world. Blood Music comprises a series of frightening transformations, and explores themes of consciousness, individuality, and the nature of reality itself.

At its outset, Blood Music focuses on Virgil Ulam. He is a brilliant but wayward biotechnologist working at the California campus of the biotech company Genetron. His area of interest is “biochips”, essentially reprogrammed cells conditioned to perform information processing - a biological alternative to silicon. He goes beyond his remit, and creates noocytes, which show the stirrings of a higher, collective intelligence.

When his superiors learn about this, they discipline him and force him to terminate his research. Refusing to see his work destroyed, Ulam takes a fateful step - he injects himself with the noocytes. Now dismissed from Genetron and unable to reconstitute the cells elsewhere, Ulam finds that his experiment is rapidly taking over his body. His behaviour changes, and he enters a relationship with a seductive woman - but his first real sexual success triggers the beginning of what amounts to an intelligent epidemic. Soon, disaster begins to sweep first California, and later the whole of North America. Society collapses. Hundreds of millions of people are contaminated and absorbed by the noocytes, which become a sprawling, conscious mass. It morphs buildings into new shapes and warps the very substance of the land. The novel’s perspective shifts, and follows a number of other characters as they confront the emerging cataclysm. Notably, these include scientist Michael Bernard, who surrenders himself to bio-containment in West Germany and Suzy, a young girl who is immune to the noocytes’ effect and wanders a devastated New York. Through Bernard, the noocytes learn to communicate with those they have not assimilated. It becomes clear that the organisms are on a steep upward trajectory in their cognitive power. While benign, their rise is unstoppable - and they approach a state of consciousness so advanced that they may no longer need a physical form. It becomes clear that the time of humanity may be coming to an end; at least humanity as we would recognise it.

Blood Music begins a little awkwardly, with opening chapters which are too full of biotech jargon. Quite quickly, though, it becomes fascinating and gathers pace towards a gripping and transcendent climax. Doris Lessing called the book “the classic sort of science fiction”, and certainly it builds on some familiar elements. Virgil Ulam, for example, is a kind of “mad scientist” archetype, updated for the 1980s. His methods are not the Galvanism of Frankenstein, but cutting-edge genetics.

The book’s contemporary setting lends it more realism and greater power to unsettle. The California environments Ulam moves within are believable. Similarly, the desperate efforts to contain the noocyte outbreak bring to mind the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. To a degree, Blood Music was prescient. By 1999, a biological computer had been created from the neurons of leeches which was capable of simple addition. This field of study could one day deliver faster computing with lower energy costs. The book also links with the so-called “grey goo” scenario, in which nanomachines consume all of the Earth’s biomass and cause the end of the world. Bear’s novel predates the coining of that phrase, which occurred in K. Eric Drexler’s 1986 book Engines of Creation. Some parts of the rapid collapse depicted in the book are genuinely frightening, such as when Suzy wakes up in her Brooklyn home to find her family - and the entire city - have been assimilated. The scenario in Blood Music is not a straightforward apocalypse, however. The noocytes are not presented as malicious, and while their effect may be terrifying it is not total destruction but rather transcendence. Humanity is essentially forced to ascend with its new creation to a higher plane of being, one not based on individuality but on incredible interconnectedness. This theme of transcendence recalls an earlier classic, Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 breakthrough novel Childhood’s End. David Langford made this connection at the time, but argued that Bear approached the theme even more successfully. In Clarke’s book, the source of transcendence is a benign alien invasion. Bear’s novel is more affecting precisely because it feels disturbingly plausible - it is easy to imagine a real-life Virgil Ulam at work, holding humanity’s future in their hands.

With Blood Music, Greg Bear delivered a lasting classic of 1980s science fiction. By building on and modernising established elements of the genre, he crafted a story which is chillingly plausible. It explores our pervasive fears about the potential for explosive change through modern science, and especially biotechnology. At the same time, there is something moving about Blood Music, perhaps because it speaks to another deep-seated feeling - a desire for the eternal, for some part of ourselves to live on forever. With this novel, Bear made a worthy legacy for himself.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

About

Exploring classic science fiction, with a focus on the 1950s to the 1990s. Also contributing to Entertainium, where I regularly review new games. Categories

All

|